After visiting the MoMA exhibition recently, I was struck by the power and dynamism of the art movements from the 1880s onwards. What also left an impression on me was that I was in the company of incredible male artists and figureheads who drove the direction of modern art. Female artists were definitely in the minority.

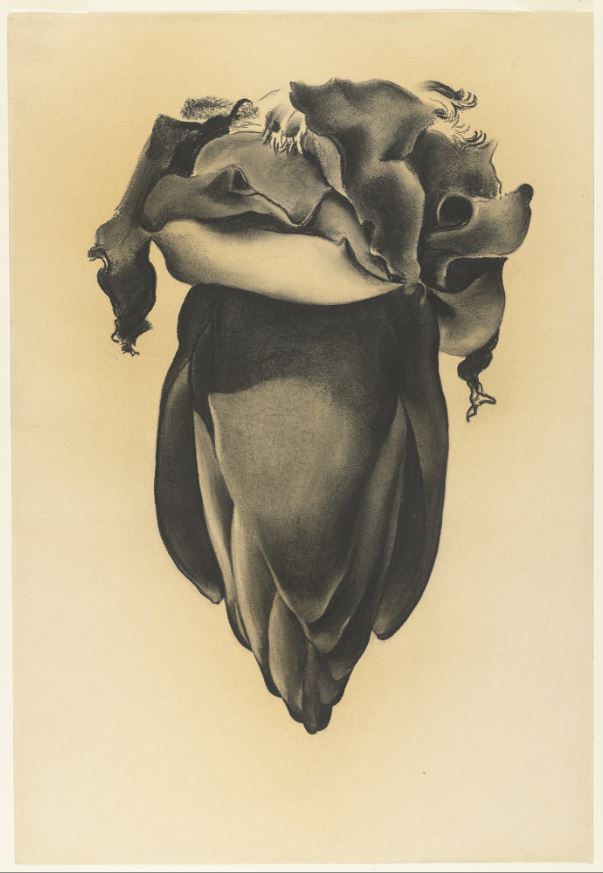

Within the exhibition, to the left of Dali’s Persistence of Time (which was so shockingly smaller than anticipated) were two modest drawings, both charcoal on paper (though with their incredible execution, you could have mistaken them for ink or oils). They were drawn by Georgia O’Keefe, America’s “Mother of Modernism”. The drawing in particular that spoke to me was Banana Flowers, pictured below. It hung silently, yet confidently on the wall, and the masterful skill and the sensitivity of the drawing compelled me to examine it up close. It was unlike any other work in the exhibition.

These drawings could have been easily missed amongst the intriguing worlds of Giorgio de Chirico and others in the same space. Hopefully this was not the case, however I wanted to highlight this one incredible drawing in this month’s newsletter.

Georgia O’Keefe (1887 – 1986) studied art formally, however she found that being taught how to draw and paint like other artists was not inspiring. After a hiatus, the work of artist/teacher Arthur Wesley Dow piqued her interest and she begun drawing and painting as she liked. She spent many months of the year in New Mexico, where she fell deeply in love with the landscape. She had an intense response to nature and a need to recreate the equivalent in art.

Her relationship with photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz proved challenging to O’Keefe when he applied Freudian interpretations to her abstract art, which, in turn, influenced art critics’ opinions. She had also posed nude for Stieglitz’ photography, and the link between exploring her sexuality through art was even stronger for it. However, this was not at all the case. She turned to creating works of recognisable objects, still lifes, and her famous close-up, large-scale flowers to try and dislodge this falsely created persona. Flowers, however, did not escape the same interpretation.

To this day there is still discussion around whether O’Keefe’s flower works depict female genitalia; in 2016, Tate Modern curated a Retrospective with 100 or her works offering alternative views on this theory. The exhibition aimed to dispel these myths by presenting works spanning six decades. The large-scale, cropped flowers for which most of the clichés about her work persist, were influenced by modern photography of the 1920s. A love for nature and landscape inarguable flows through her work and the exhibition portrayed this as her most persistent source of inspiration.

Written by Lauren Ottaway