Australian artist, Gordon Bennett (1955 – 2014), spent most of his life and career struggling against how he was perceived. This struggle went from being an experience of extremely low self-esteem to producing a powerful and highly articulate art practice. Several years after his untimely death, Bennett’s work illuminates our understanding of how identity operates in our society.

Bennett was raised in a cultural climate where, until he was twelve years old, his Aboriginal mother was not a legitimate Australian citizen. For, it was not until a 1967 referendum when ‘Aborigines’ where given the right to be counted in the census as Australian citizens. Until Bennett was in his early teens he believed his father’s Scottish and English origins was his only heritage. He then realised his mother was Aboriginal. This began Bennett’s struggle with his self-identity, for at this point, his identity shifted from identifying with being in the mainstream of Australian society, to being Aboriginal. Overnight, Bennett went from being the ‘cowboy’ to be the ‘indian’, from ‘light’ to being ‘dark’. Of course, the binaries of dark and light are not true or real identities, but their ingrained pervasiveness and how he was perceived by others, created turmoil for Bennett.

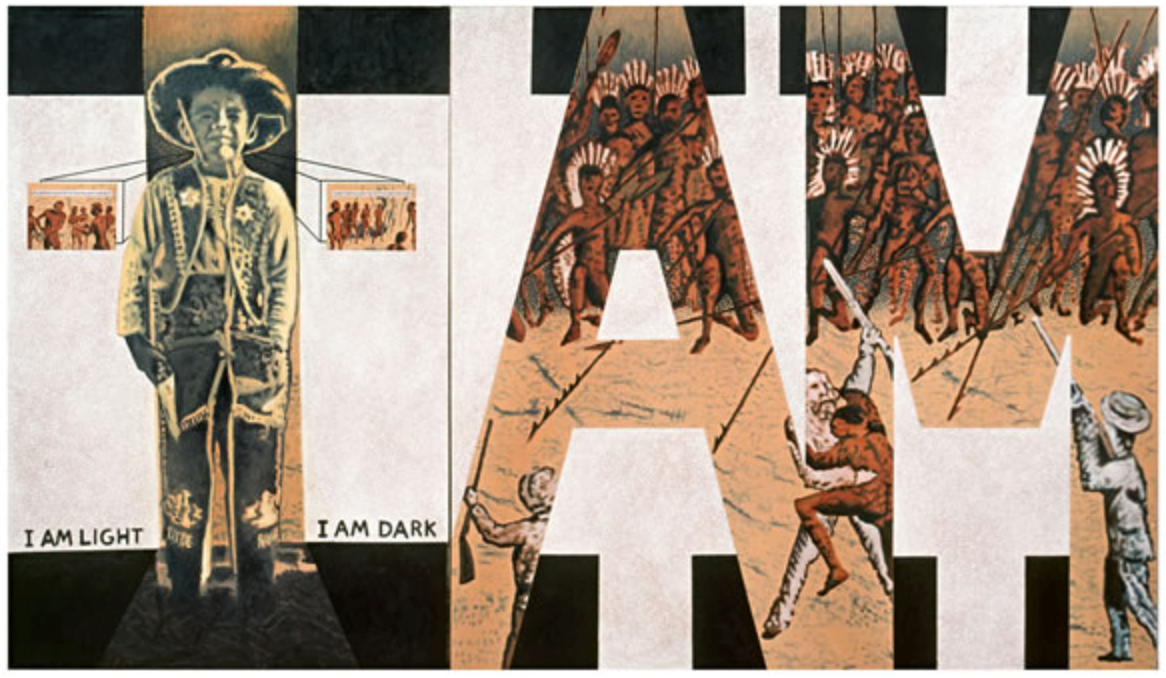

Gordon Bennett, Self portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys), 1990, oil on canvas, 150.0 x 260.0 cm

Private collection, Brisbane © Courtesy of the artist Photography: Phillip Andrews https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/gordonbennett/education/02.html

Bennett’s 1990 painting, Self portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys) describes this turmoil well. There he is, as a boy in a cowboy uniform, seemingly oblivious to the complexities of social identity operating upon him. But it is Bennett, the man who has chosen to paint this as his Self portrait. A Self portrait that is not attempting to describe his own physical appearance, rather it is describing how he has been represented by others. Bennett appears caught between the words, I AM LIGHT, I AM DARK. A colonial battle is placed in the background of the right panel. Bennett’s own identity has become a colonial war. The title (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys), suggests that this is an expression of desire to be perceived as being on the right side, the light side, the good guys. Bennett seems to be describing himself as torn away from the mainstream identity he thought he enjoyed and cast into the place of being ‘other’, the bad guy, the ‘indian’. But the painting is not a lament and Bennett never comes across as feeling sorry for himself; rather it is about the exposure of the structures of identity operating within Australian society. These structures are primarily based on a binary; if you are not part of the mainstream, you are something else, you are ‘other’.

When Bennett left school, he took on an apprenticeship with Telecom. During the years of working with Telecom, he witnessed considerable racism towards indigenous Australians until he quit to then go on to art school at the age of thirty. After later becoming well known as an artist with a powerful Post-colonial project, Bennett had to struggle against the politics of identity that continually labelled him as the ‘Aboriginal artist’ or ‘urban Aboriginal artist’. During considerable success through the 1990s, Bennett just wanted to be known as an artist, refusing to be labelled by race. It was not until he gained international recognition in the last years of his life, that Bennett began to be considered a ‘contemporary artist’.

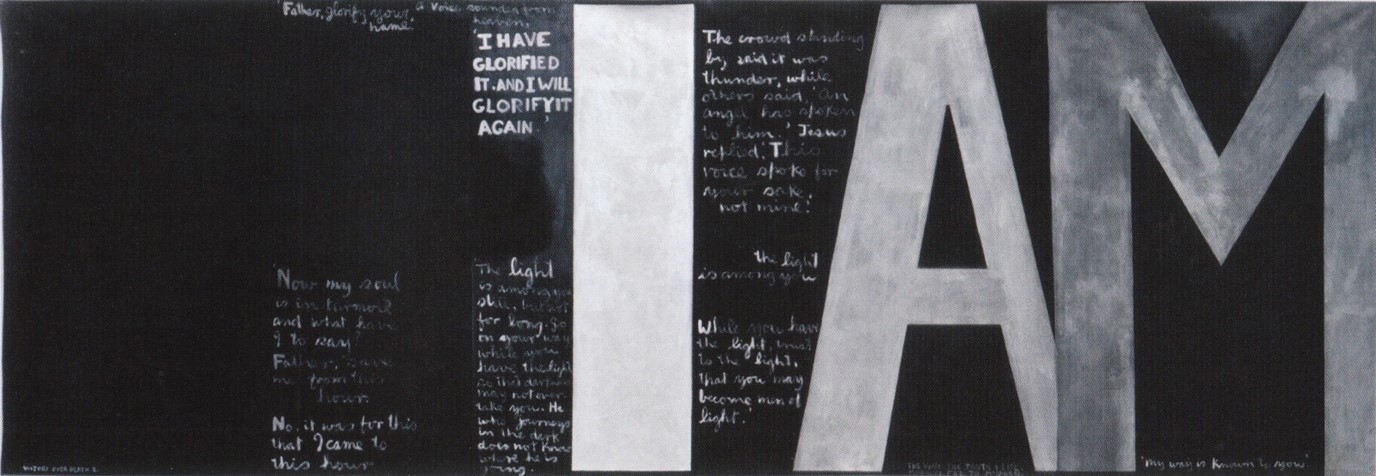

Colin McCahon,Victory over death 2 1970, synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 207.5 x 597.7 cm

Colin McCahon,Victory over death 2 1970, synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 207.5 x 597.7 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the New Zealand Government 1978

© Colin McCahon Research & Publication Trust

The large letters I AM, are appropriated from New Zealand artist, Colin McCahon’s (1919–1987) Victory over death 2, of 1970. McCahon uses ‘I AM’ to question his own Christian faith and subsequent identity. ‘I am that I am’, from Exodus 3:14, is God’s response to Moses who had asked after God’s name. God’s response is actually a refusal to a name, or to be named. With letters towering at over two meters tall, McCahon’s monumental I AM impressed me powerfully when I saw it as a teenager. It seems to embody the sense of God being origin and of being infinity, all without being named.

Bennett’s appropriation of the I AM works on several levels. Firstly, it references a Judeo Christian tradition of spiritual identity based in God as origin and seems to be referencing a similar quest for identity as McCahon has. Except Bennett appears to be locked out from I AM by the experience of being labelled the ‘other’ identity. On another level, Bennett is quoting the words of a God who refuses to be named. Bennett’s painting is all about names and Bennett seems to be indicating that he, as a person, cannot be defined by the names being applied to him. So it seems that, if as in the Judeo Christian tradition, men and woman are made in the image of God, a God who refuses to be named, then Bennett exists beyond the names being placed upon him. With two powerful words Bennett seems to indicate his true identity as existing beyond all that has been placed upon him. Bennett refuses to be named.

Colonisation has been effective in taking hold of land, peoples, and resources by stripping away a true, complex and self-articulated identity expressed through culture, ritual and language. It replaced these identities with an imposed name, which, in many different ways, disempowered the bearer by denying their true nature. Bennett’s work often articulates the oppressive mechanics of identity in Australian society which have their origins in a colonial society. Self portrait (But I always wanted to be one of the good guys) gives us a clearer understanding of how these imposed identities operate, but it also goes deeper by indicating the nature of the human person as being an un-namable I AM.

Written by Marco Corsini