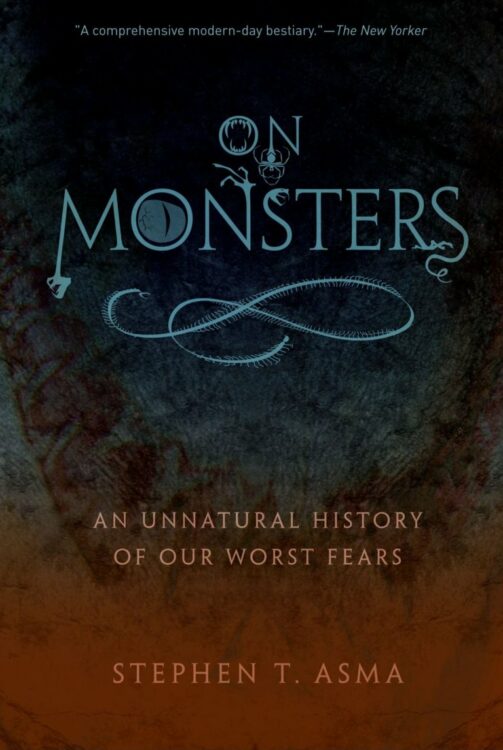

I recently explored a very interesting book titled On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (2009) by Stephen T. Asma, a professor of philosophy at Columbia College Chicago. A comprehensive piece of research on the subject (from a Western perspective), it begins by outlining certain key general characteristics of monsters.

It further divides the topic into five main parts: ancient monsters, medieval monsters, monsters examined through the lens of science, psychological monsters, finally discussing the identity of monsters today with a view to the future.

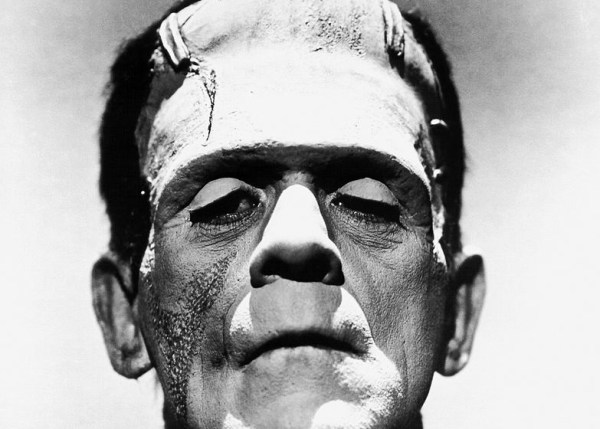

As the book opens, Asma mentions how our phobias, evolutionarily speaking, have been advantageous for human survival. They incite us to protect ourselves. The monster is the figure onto which we project our fears. Asma points out two basic ways in which the monstrous phenomenon could be understood—it is unthinkable and unmanageable. That is, it leads to a breakdown of intelligibility. When something/someone is monstrous it cannot be processed by our rationality, prompting us to question how can they do it? Like Pol Pot and his men in Cambodia. The monstrous also unleashes chaos, like the invention of Victor Frankenstein. It may not necessarily be inherently evil but it can, over time, take a turn towards malevolence. It can be dangerous to us, disturb our sense of order, peace, safety and security.

Beyond such fundamental characteristics, the monstrous has assumed different meanings at different times, going from superficially physical to deeply spiritual. The concept has shifted in human imagination and art over the centuries. Asma explains further: “Monster is a flexible, multiuse concept. Until quite recently it applied to unfortunate souls like the hydrocephalic woman. During the nineteenth century “freak shows” and “monster spectacles” were common; such exploitation of genetically and developmentally disabled people must be one of the lowest points on the ethical meter of our civilisation.

“We have moved away from this particular pejorative use of monster, yet we still employ the term and concept to apply to inhuman creatures of every stripe, even if they come from our own species. The concept of the monster has evolved to become a moral term in addition to a biological and theological term. We live in an age, for example, in which recent memory can recall many sadistic political monsters.”

Here are a few examples of the monster—with the meanings behind them—from each of the five parts of the book:

(1) Ancient Monsters

In antiquity, as the continents were farther away for lack of adequate transportation and communication, the sense of the “exotic” was particularly pronounced. Monsters were numerous and varied—cyclops, griffins. Many were exaggerated, embellished versions of creatures that were believed to exist in foreign lands. Other races were also considered monstrous. Example, the Greek physician Ctesias reported an umbrella-footed race of creatures “who have only one leg and hop at astonishing speed and who also lie on their back and raise their large foot to act as an umbrella against inclement weather.”

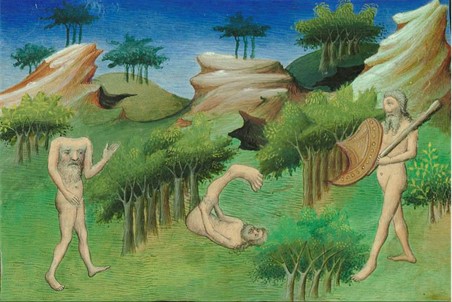

(2) Medieval Monsters: Messages from God

With the Christian worldview, monsters were recast as “God’s lackeys”. They were now part of a fallen world, originally created good by a benevolent omnipotent God. If they had taken the path of corruption out of their own will, they were even capable of redemption. They were sometimes supposed to have a specific purpose, having been made by God to teach us how to love the ugly, the repulsive and the outcast. Some monsters—like the Leviathan and Behemoth—represented the terrifying, unknowable aspect of God. Monsters, overall, were no longer random as under older pagan systems. They were imbued with more significance and purpose. The medieval mindset did lead to one particularly disturbing series of events—witch hunts. From the Inquisition of the Late Middle Ages to the New England trials of the 1690s, witches were the monsters foremost in the social imagination, deemed to be special vessels of demonic ill will.

(3) Scientific Monsters: The Book of Nature is Riddled with Typos

Allegory and fantasy slowly gave way to more objective zoology. In the early seventeenth century, the gradual turn from magical thinking to science had major implications for monsters. The English philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon (1561-1626) said: “We must make a collection or particular natural history of all the monsters and prodigious products of nature.” He argued that specimens must be amassed in warehouses of study and systematic knowledge derived from them.

Subsequently, there were intense discussions on design, chance, mutations and teleology in nature, and the role of divine will. In the nineteenth century, we find the emergence of “freaks” (a term that would be considered very offensive today)—individuals with physical deformities due to unusual medical conditions or body modifications. The American showman and businessman P. T. Barnum (1810-1891) established his grand travelling circus, menagerie and museum of “freaks” around 1870.

(4) Inner Monsters: The Psychological Aspects

Later, with writers like Edgar Allan Poe, E. T. A. Hoffman and H. P. Lovecraft, and philosophers like Kant, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche—and finally with Freud—monsters settled into their new abode of “human psychology”, having worn out their welcome in travellers’ tales, religion and natural history. The depth and complexity of the cosmos was, in a way, transferred to the mind. As the source of evil actions was hidden from plain view, a situation emerged wherein it was hard to detect and understand monstrous personalities. In this section, Asma gives the example of John Wayne Gacy (1942-1994), an American serial killer who raped and murdered thirty-three boys in the 1970s. Gacy, who worked part time as a clown, ensnared his victims with bogus magic tricks.

(5) Monsters Today and Tomorrow

Finally, with the world becoming more connected in the twentieth century, there was a greater awareness of differences among cultures. And we witnessed deadly conflicts over the decades—from the Holocaust to bloodbaths in Yugoslavia to the dehumanisations of the Iraq War—all revolving around the fear and hatred of “the other”. It is also interesting that Hollywood popularised the “zombie” (actually a character from Haitian folklore)—ravenous undead that blast their way through walls to devour all your resources and overpower you—with rising immigration rates in America. Academic and public discourse perpetuated ideas that magnified dissimilarities and anticipated the possibility of struggles between peoples. For instance, American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington (1927-2008) famously proposing his “Clash of Civilisations” theory about the post-Cold War new world order.

Now, with technological progress, the monster has taken new forms. Asma ends his book with notes on robots, mutants and posthuman cyborgs. Most pertinent is the discussion on “disembodied minds”, given our era of Artificial Intelligence. The specific face of the monster will continue to change with period and place, but a recurring leitmotif runs through all monsterology—the question of how we meet the threat, which is entirely up to us to decide and can evolve as well.