In conversational English, the word “medieval” carries plenty of negative connotations. Many of us see that era in Europe as a time of superstition, stagnation and fear that was, thankfully, superseded by a much-needed “Enlightenment” in the 1700s. Although such an impression of the Middle Ages continues to prevail among the masses, serious historians now maintain that the term “Dark Ages” should be applied to just the period immediately following the fall of the Roman Empire (around the years 400-500). The span between the late 700s and 1500, it is understood, brought a considerable amount of social stability, political organisation and educational activity, including the flowering of the first universities.

For all its flaws and challenges, medieval Europe was a fascinating place and epoch. And medieval men and women, full of faith, adhered to a conception of the cosmos that was theatrical and imbued with sacramental meaning. They constantly looked for proportions and patterns in Creation and believed in the interconnected of all things. In their worldview, matter transcended itself to communicate truths of supernatural importance.

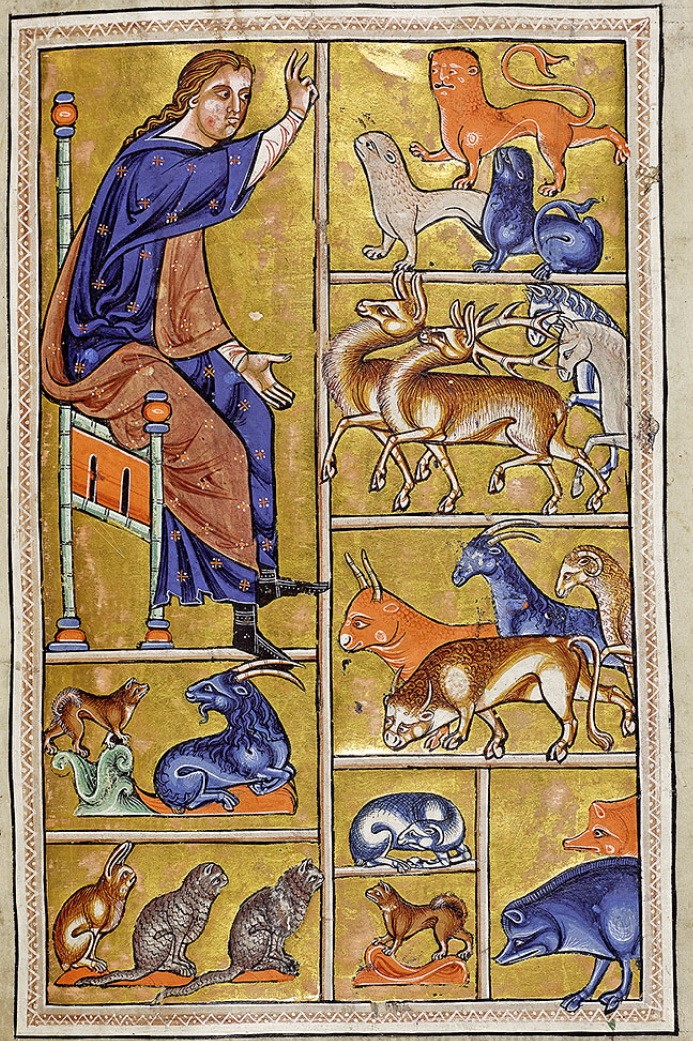

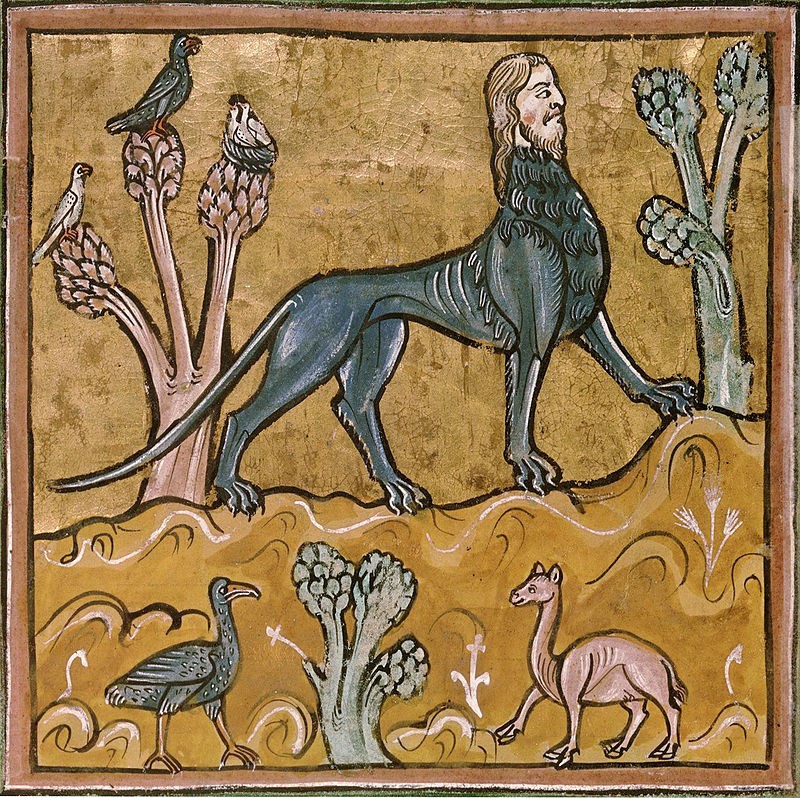

According to the Italian scholar Umberto Eco (1932-2016), the philosophers and theologians of the period believed in a universe that was filled with light and optimism. In both poetry and painting, medieval people portrayed themselves as living in extremely bright surroundings. We can see this in the illuminated manuscripts. Eco writes in History of Beauty (2004) that even though they were probably executed in environments “where the gloom was barely relieved by the light from a single window, they nevertheless brim with light, with a particular effulgence engendered by the combination of pure colours: red, azure, gold, silver, white and green, devoid of nuances or chiaroscuro.”

There is a category of the medieval illuminated manuscript that stands out: the bestiary, known in Latin as bestiarum vocabulum. The bestiary, as the name suggests, was a compendium of beasts, real and legendary, that contained descriptions and illustrations accompanied by moral lessons. Although the document goes back to the 2nd century (the first one was in Greek, titled Physiologus), it became popular only in the Middle Ages. Nature was perceived to be God’s second book of revelation after the Bible, and animal life, in all its variety and adventure, was interpreted through an allegorical lens and investigated for hidden spiritual/religious significance.

Professor David Brown of the University of St. Andrews, Scotland explains in his book God and the Enchantment of Place (2004): “Even today some of these stories survive in the corporate memory, as, for instance, the parallels between Christ feeding us in the Eucharist and the pelican reviving its chicks with its own blood. So too do some of the associations, such as the snake or the ape with evil, the hare and rabbit with lust and fertility or the dog with faithfulness. On the other hand, even those well versed in Scripture might have difficulty conceiving how particular biblical verses were expanded to make the eagle a symbol of renewal, the stag of perseverance, or the lion of resurrection, far less of the lessons without biblical underpinning as in the association of the beaver with chastity, the hydrus with salvation, or the peacock with resurrection. Although in the latter cases ultimately derived from paganism, it would be a mistake to dismiss such borrowings as no more than that, for in the process of adoption they have usually also been thoroughly Christianised… Likewise the strange hybrid creatures that are depicted were far from being cultivated as mere ‘freaks’ but more as object lessons or even as themselves worthy of salvation.”

Read an excerpt from a bestiary kept at Bodleian Library in Oxford, translated by historian Richard Barber: “Deer by nature like to change their homeland, and for this reason seek new pastures, helping each other on the journey. If they have to cross a great river or lake on the way, they place their heads on the hindquarters of the deer in front, and, in following each other, do not feel hindered by their weight. And if they come to a place where they might get dirty, they jump rapidly across it. Another peculiarity of their nature is that after they have eaten a snake, they hasten to a spring and, drinking from it, their grey hairs and all signs of old age vanish. The nature of deer is like that of the members of the Holy Church who leave this homeland (that is, the world) because they prefer the new pastures of heaven, and support each other on the way; those who are more perfect help their lesser brethren through their example and good works, and support them. If they find a place of sin, they spring over it at once, and if the devil enters their body after they have committed a sin, they hasten to Christ, the spring of truth, and confess, drinking in His commandments, and are renewed, laying aside their old guilt.”

Such presentations might strike us moderns as too fanciful. But in our disenchanted world where noisy engines have expelled much mystery from the natural world, it is refreshing to encounter such grandeur, luminosity and sense of wonder.

Written by Tulika Bahadur