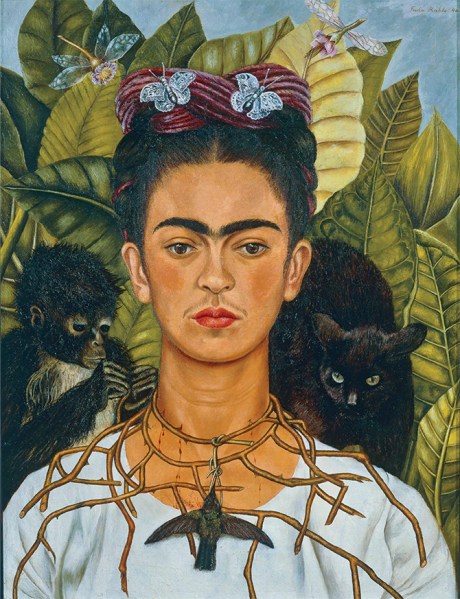

Harry Ransom Center, Austin, Texas, US (Fair Use)

There is a quote by Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) that I find very interesting: “They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.” The truthful depiction of “reality”—as we normally understand it—in the arts is simply known as Realism. It is a factual representation of the world, one that is free of phenomena that might seem unbelievable or fantastical or supernatural, a reflection of things that exist, of things as they are, as they are seen, heard and felt.

Realism, if you search it out in Google Images, will yield results showing peasants in fields, city-dwellers in cafés, fruits on a table, a family at supper. Lots of brown, yellow, some green. Historically, the movement began in France in the 1840s (around the 1848 “February” Revolution). Fairly enough, it was a reaction to the emotionalism and exoticism of the Romantic period. Realism sought to portray every social class, ordinary life and labour during a time of rapid industrialisation with accuracy, eschewing depictions that were idealised or artificial, and confronting aspects of existence that were uncomfortable or harsh.

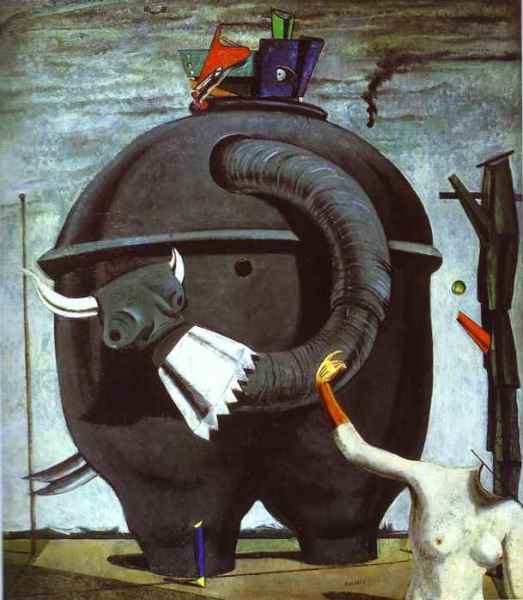

On the other end of Realism is Surrealism—having grown out of “Dada” experiments in Switzerland following World War I that revolted against the logic of modern society and capitalism and embraced nonsense. Surrealism, as we know, is a style that merges dream and reality, the rational and the irrational, the conscious and the unconscious, and, as a result, breaks through predictability and patterns. Its strange juxtapositions unsettle our sense of order and expectation.

When I look at Frida Kahlo’s work, it seems as an enterprise, that it could be placed between Realism and Surrealism (perhaps Magic Realism is the best term—as some have described it?). She draws inspiration from the events of her own life but her art clearly isn’t all stark and factual, which means we cannot straightaway call her a Realist. Also, it isn’t jarring and beyond reason, so we cannot consider her an outright Surrealist—her paintings retain a certain dreaminess, embellishment, strangeness and otherworldliness but her intention isn’t to create an effect of surprise or shock. Rather, it is an invitation to a deeper immersion in her complex and multi-layered being.

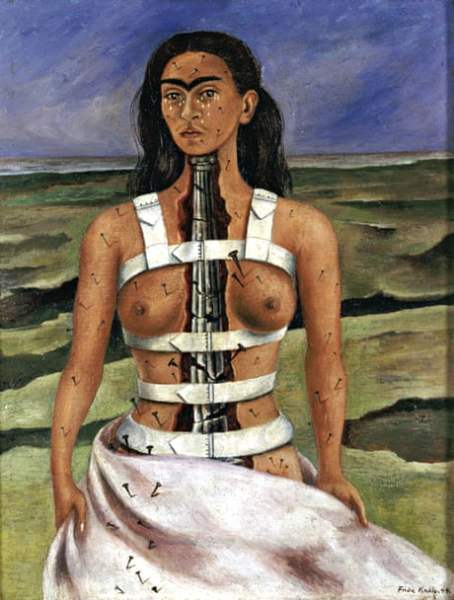

Kahlo is in the middle of extremes. The Realist side of her openly acknowledges the human condition with its travails and tragedies. Having struggled through polio in childhood, a severe road accident, a tumultuous marriage (to artist Diego Rivera) and childlessness, she exhibits her suffering before the world without shame. For example, in The Broken Column, her injured spine becomes an Ionic column.

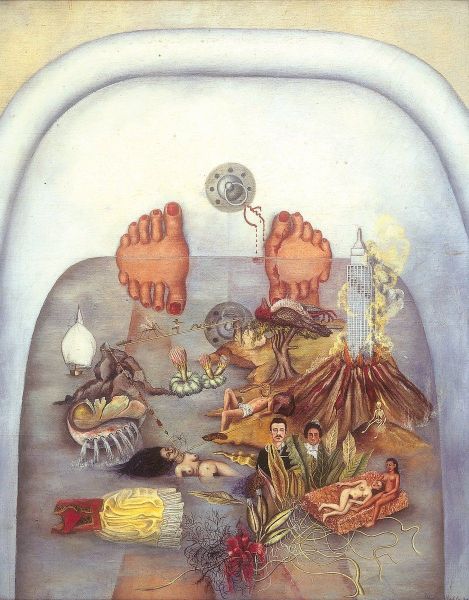

On the other hand, her Surrealist side celebrates the human ability to indulge in reveries and hallucinations, and emancipate herself, albeit temporarily, from the weight of life through the sheer thrill of imagination and creativity. In What the Water Gave Me, we find a mysterious association of flora and fauna, a volcano, a dress, images of Kahlo’s German father and Mestizo mother, a modern skyscraper, references to torture, erotic encounters, death and dance. The entire theatre is acted out in a bathtub wherein the artist lies submerged.

In her visuals, Kahlo revealed a two-fold reality—of the body and the mind. She presented the sensuality, fragility and stamina of her outward physical presence (which was objectively available to everybody) alongside the wild, wide-ranging, sometimes confused, activity of her hidden inward dimension. And she deemed this latter invisible, intangible, volatile domain as true and important as the former (who on earth considers the meaningful thoughts he/she thinks daily under the shower as fake or false or unreal?). In Kahlo’s context, I remember a powerful question asked by Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007): “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

Kahlo is enduringly popular in a very special way, I think, because she gave us a reality that was more expansive than the most faithful and exact instances of Realism. That movement showed us peasants toiling in the fields and that alone, it stopped before attempting to explore the drama of their internal faculties. Also, Kahlo’s reality, despite its bits of wild fantasy, had a concrete form and personality that made it more immediately accessible to the viewer than a lot of Surrealism with its bewildering amorphousness. She successfully demonstrated these lines of Neil Gaiman: “Everybody has a secret world inside of them. All of the people of the world, I mean everybody. No matter how dull and boring they are on the outside, inside them they’ve all got unimaginable, magnificent, wonderful, stupid, amazing worlds. Not just one world. Hundreds of them. Thousands maybe.”

Written by Tulika Bahadur.