Rijksmuseum © Olivier Middendorp 2019

Before I left for Europe, my father told me that I had to see the artwork of one of the greatest Spanish artists, Diego Velázquez. So it was a wonderful surprise when I stumbled on an exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam called ‘Rembrandt-Velázquez – Dutch & Spanish Masters’, a comparative exhibition including a collection of Dutch and Spanish artists from the 17th Century.

Each charcoal coloured wall had two or three masterpieces hung next to each other. The curators had identified a key idea that they shared and chose particular paintings to be exhibited together. The most unique aspect of this exhibition was that all the Dutch and Spanish Masters lived through and created their art during the Eighty Years’ War. This war began because the King of Spain, Philip II, was persecuting a religious minority of Calvinists in the Netherlands. As Spain was predominantly Catholic, the King felt it was his duty to fight Protestantism and protect Catholic values throughout the empire. After eight bloody and murderous decades, the Dutch eventually seceded from the Spanish Empire and declared their independence in 1648.

Rijksmuseum © Olivier Middendorp 2019

The complicated history of religious tension between Spain and the Netherlands is articulated in the first pairing of the exhibition which is Agnus Dei by Francisco de Zurbarán and Interior of the Sint-Odulphuskerk in Assendelft by Pieter Jansz Saenredam (pictured above). The Spanish artist draws on traditional Catholic iconography of the lamb as a symbol of Jesus Christ. In contrast, the Dutch painter focuses on the speaker at the pulpit as Protestants believe that all religious teaching should be centred on the Bible. Furthermore, the simple decoration of the Protestant church reveals their contestation of the Catholic veneration of Saints and Mother Mary through the lack of icons and imagery that adorn the walls of Catholic churches.

Although visually and technically quite different, both paintings demonstrate a fundamental truth of which the artists appear convicted. As these paintings sit side by side it seems simple to point out the similarities in the way that religious ideas are conveyed. This is the unique power of the exhibition. It allows conversations between the artists through their masterpieces that would not have been possible in the time they were intended.

However, these paintings being exhibited together also highlights a weight of pain. So much time has passed that we are unfamiliar with the suffering endured due to the fundamental differences that caused the Eighty Years’ War. Yet, these images intimately reflect the pain of loss, the fight for one’s religion and the struggle for freedom that permeates not only this war, but the multitude of conflicts throughout history caused by religious division. The paintings transcend their time and represent the individual’s perseverance and resilience for their faith and culture. We cannot imagine what these images sitting side by side could have meant to the people who lost everything due to the Eighty Years’ War.

Rijksmuseum © Olivier Middendorp 2019

As we continued to weave through the viewers, a series of four paintings by Velázquez and Rembrandt appeared. The structures and pigments of each work resembled the next with only the majestically draped clothing slightly altered. It is hard to believe that these were not painted by the same artist, or at least influenced by each other. Velázquez and Rembrandt never met despite being Masters of their craft in the same era. Here you can almost hear them chatting as friends and colleagues, sharing techniques and enjoying the craft they both love. As the Netherlands broke away from Spanish rule, a new society was created that was founded on citizenship. Dutch painters such as Rembrandt worked for a free market, as seen in these portraits that were commissioned by wealthy, newlywed merchants. Spain remained more traditional and was ruled by an influential Royal House. Spanish artists such as Velázquez were primarily commissioned by the Church and the King to create their artwork. This is evident in his subjects who were nobles in the Royal Court.

The social and political differences in the structure of these societies gave rise to the selection of subjects by the two Masters. However, these unique positions of status could have influenced their depiction of the subject so much more. The nobility could have been shown with a valuable symbol to demonstrate their high position in society. The newlyweds could have been positioned to show the beginning of their future together. Instead these five incredibly wealthy and powerful individuals, though living in different contexts, are painted with the least embellishment possible. They stood before us almost life-size, revealing only our shared human experience.

Rijksmuseum © Olivier Middendorp 2019

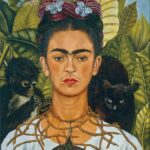

The way that these individuals were crafted speaks volumes about the crafters themselves. On the next charcoal wall, we see Velázquez and Rembrandt’s self-portraits exhibited next to each other. The paintings parallel each other both visually and emotionally. Dark brown hues encase detailed, creamy faces. Their steady gazes are locked with the viewer. Both paintings are humble and unpolished. They show the raw talent of the artists and give us a unique view into the depths of life that the artists experienced.

Velázquez and Rembrandt both played leading roles in their own societies. Velázquez held a high position in the Spanish Court and Rembrandt was an influential painter and printmaker. The curators eloquently note that ‘while their social environments were worlds apart, their artistic ambition and unsurpassed ability to fathom the human depths of their models hardly differed’. Three hundred years after the war has ended, it is a joy to listen to these Masters conversing and to find with them the similarities that surpass their differences.

Written by Bella Corsini.