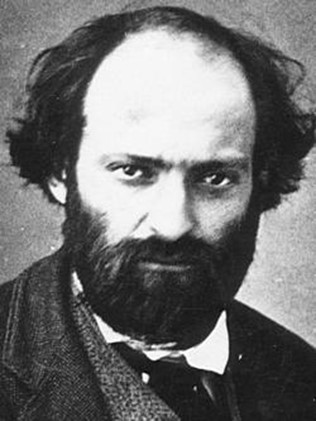

Art fascinates. In a sense, spontaneity and intuition trumps intellect and I am drawn to the pioneers in art who threw away the rulebook. They wrote new stories. Paul Cézanne is one of those pioneers. He delineated modern art before anyone knew it existed. Turned the world of art upside down, inside out. Opened the door for expressionism, fauvism, cubism and abstract expressionism.

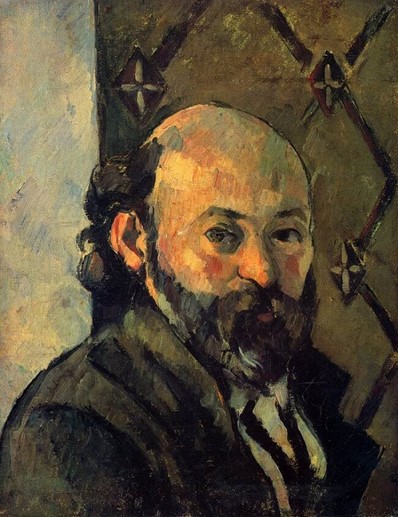

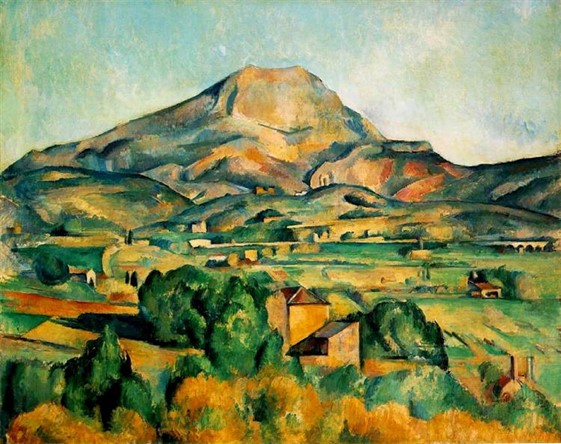

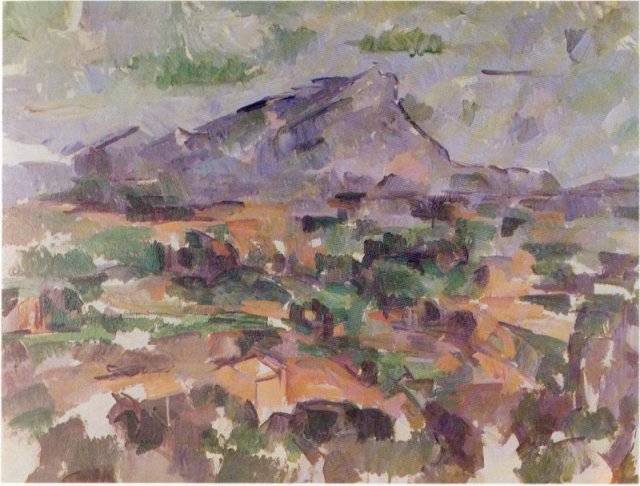

Jonathan Jones, of the Guardian, wrote that Cézanne “invented modern art by looking hard at mountains, ruins, rocks and apples.” Cézanne painted Mont Sainte-Victoire in Southern France at least 60 times. The progression of his art between 1895 and 1906 can be seen in the three versions of Mont Sainte-Victoire below. The progression of colour, shape and abstraction is profound. Cézanne reduced everything he saw into a variety of disparate identifiable geographical shapes. Look at the rocks and boulders in his landscapes. The movement from Cézanne to fauvism, cubism and abstract expressionism is logical, if not inevitable. In a sense Cézanne separated his paintings from the object that he was painting. It encouraged modernist artists to look deeper, including within themselves.

Cézanne was in the right place at the right time and went on to have a profound influence on generations of artists. The second half of the 19th century in France bristled with creativity. It was the age of poets like Baudelaire and a precocious Rimbaud. Musically there was Debussy, Ravel and a quirky Eric Satie. These artists rubbed shoulders, influenced each other. Cézanne went to school with writer Emile Zola. He met Manet, Monet and other Impressionists in Paris as well as Post Impressionists like Van Gogh and Gauguin. “Cézanne, he’s the greatest of us all” said Monet. Van Gogh was living in France and wrote his brother about Cézanne. Most notably, Cézanne had a seminal influence on two giants of 20th Century art, Picasso and Matisse. Picasso said Cézanne’s influence gradually flooded everything. He said that Cézanne was like a mother hovering over. Matisse referred to Cézanne as “the father of us all”. Cézanne influenced cubism by painting nature with geometric shapes and by painting a subject from different perspectives.

Cézanne wrote to the younger artist Émile Bernard. “The painter gives concrete expression to his sensations, his perceptions, by means of line and color.” And just like that, he stepped away from accurate depiction of visual reality. Artist, art critic and writer, John Berger, said that Cézanne was a prophet, who had a love affair with the visible. He wrote that Cézanne’s paintings were like a diagram containing a booklet of instructions (metaphorically) about how to use a new appliance or tool. As we look at Cézanne’s work we begin to be “instructed” in the way he perceived the world around him. We see the process of looking, of perception and of making in the very process and structure of the work.

The “love affair with the visible” can also be described as “deep looking”, a technique that allows you to go beyond the surface of what you see. Jones analysed Cézanne’s painting, Hillside in Provence which hangs in London’s National Gallery. He wrote – “A rapid glance might tell you this is a tranquil picture of the Provençal countryside. Look again. It is rather an incredibly charged and overwrought personal struggle with the view in front of Cézanne’s eyes. Every dab of colour seems to be the result of days of thought and internal argument… By the time he has won his battle with the landscape, Cézanne has turned it inside out… Nothing is certain. In the distance, green-and-olive fields become squares and rectangles of green and olive, painted as the heat haze has simplified them in his eyes, transformed into abstract visual notations.”

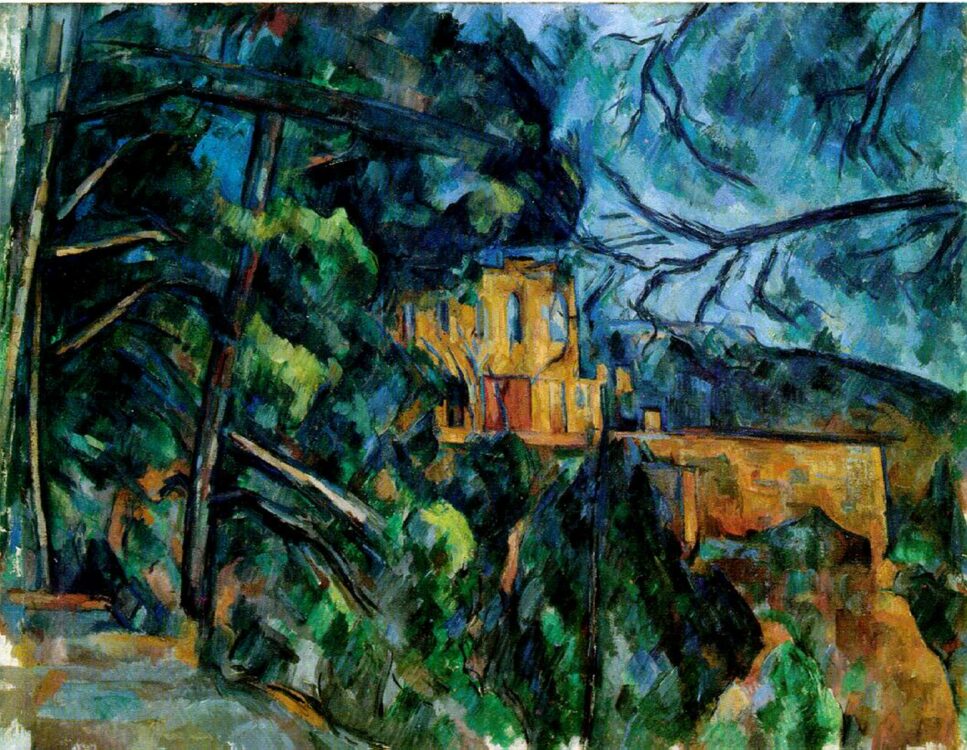

Sister Wendy Beckett discusses Cézanne’s Le Chateau (1900/1904). The detail in the painting shows his characteristic diagonal brushwork. She notes that Cézanne’s paintings had a tension between actuality and illusion, reality, description and abstraction, reality and invention. The disparate elements in the painting are unified by the way he uses paint. The blue of the sky can be found in the trees, the rocks and the windows of the chateau. Some tree branches are suspended and not connected to trees. Beige rectangles hang in the air, separated from a beige building. Splashes of green in a blue sky.

Berger wrote that Cézanne believed that the visible, was a construction combined by nature and ourselves. For Berger, the black in Cézanne’s paintings was akin to a box that contains everything in the visible world. He said that Cézanne unpacked his black box by saying that a landscape “thinks itself in me and I am its consciousness…Colour is the place where our brain and the universe meets.” It seems that according to Berger, the black is all things and all possibility, not yet revealed. The world emerges from darkness in its observation, just as the brush stroke catches a colour in the moment it is seen. Cézanne’s paintings are made of a series of recorded perceptions of the world which take the elements of colour and structure and lay them down, painstakingly, slowly. Cézanne’s work therefore simultaneously holds within it, the limitations of observation and representation, while also opening up for the generations to come, the creative possibility of that same subjective perception.

Written by Luisa Blignaut.