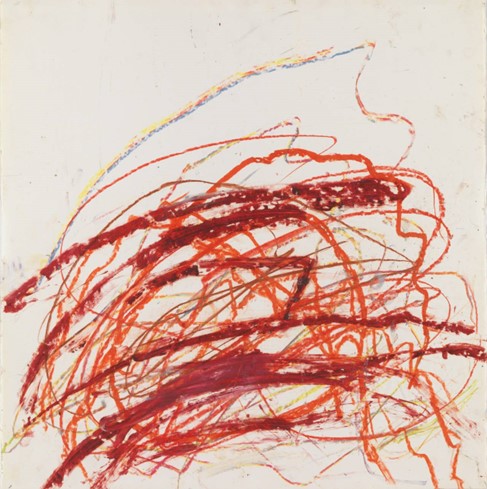

Cy Twombly’s oeuvre covers a wide range of subjects, particularly history, ancient myths and poetry. Twombly used a range of mediums to work with, including house paint, oil stick, wax crayon and Bic ball point pens and was a curious and independent mind that ignored conformity. Initially, I saw random scratches, lines dancing on an edge, splashes of colour, graffiti-like scribbles, marks and stains. The writing on his paintings and drawings often becomes illegible and disintegrate. These first impressions left unanswered questions. Twombly haunted me and many commentators agree that Twombly’s art is notoriously difficult to like. Was he writing or drawing? Twombly was enigmatic and seldom gave interviews. Allusive and elusive. He does not elucidate.

Twombly was born (1928) and raised in Lexington, Virginia. He commenced formal studies in art at the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston in 1948. He said it was a factory for precise anatomy drawings void of any form of self-expression (Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly by Joshua Rivkin). He left Boston in 1949 and attended the Washington and Lee University in his hometown during 1949 and 1950. In 1951 he attended the Art Students League of New York where he met Robert Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg suggested that Twombly go the Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Black Mountain was a veritable “who’s who” of Modern art in the 1950’s. Twombly went on study with abstract expressionist artists like Robert Motherwell, Willem De Koning and Franz Kline.

From 1953 to 1954, Twombly was drafted into the army – an unhappy experience. His cryptographic work was too vague for the military. On weekends he went to a motel, where he drew in darkness. He wanted to feel what he did, but not see. The process mattered, not the end. He deliberately un-trained his graphic skills. Drawing in darkness resulted in unique lines that became integral to his style. Twombly said every line he made, was “the actual experience” of making the line, adding: “It does not illustrate. It is the sensation of its own realization… It’s more like I’m having an experience than making a picture.” (New York Times, 6 June 2011). Every line seems to have a mind of its own. In 1957 Twombly left New York, the de facto centre of modern art and to returned to Rome where he met the Italian artist Baroness Tatiana Franchetti. They married in 1957 and had a son.

Twombly’s art is characterised by paradoxes between word and painting, between drawing and writing. Twombly often translated poems into paintings and drawings. Mary Jacobus quotes Twombly stating that,

“I like poets because I can find a condensed phrase……I always look for the phrase.”

During 1981 Twombly made ten drawings called the Gaeta Set (for the Love of Fire and Water). They resulted in a collaboration between Twombly and the Nobel Prize winning Mexican poet Octavio Paz. The drawings and poems published as a book in 1993 titled Octavia Paz, Eight Poems, Cy Twombly, Ten Drawings. Neither Twombly, nor Paz knew that their work would converge into a book. Paz selected the poems that would accompany drawings. Mary Jacobus, writes that the paintings and poems may not have been designed to illustrate each other, but in conjunction, they change both drawings and poems.

A glance at Twombly’s works, show that he scribbled the names of poets and parts of poems. See Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor). The painting is 15 meters long. In the painting Catullus leaves the shores of Asia Minor (Turkey) in a boat to sail across the sea. Art historian, Thierry Greub quotes Twombly as saying, “I think of the painting’s movement as falling…. It cascades and it exits on the left. The painting is about life’s fleetingness. It’s a passage. It starts on the right and as you move to the left it just goes out.” (Gagosian Quarterly, Summer 2021). The painting appears to be describing the departure of Catullus, as an impression left in time.

When Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), was shown in Houston, a French woman undressed in front of it. “The painting makes me want to run naked” she later wrote in the guestbook. Twombly stated that her reaction “delighted” him. “That’s pretty good. No one can top that”, said Twombly (Ralph Blumenthal, The New York Times, 3 June 2005). In the poem, Catullus mourns the death of his brother in Asia Minor and Twombly quotes a line from one the poems as the title of his painting.

Time and impressions from the past are central to Twombly’s work. Twombly stated that, “The past is a springboard for me. . . Ancient things are new things. Everything lives in the moment, that’s the only time it can live, but its influence can go on forever.” (Press Release, Gagosian Gallery, New York, 20 February, 2018). The passage of time and the impression left behind is also reflected in the comments of Richard Dorment, art historian and art critic for the Daily Telegraph, who wrote that, “Twombly’s art is about the evanescence of experience. He was a rare spirit, an artist who painted like no one else. His subject was time, its passing and what it leaves behind.”

Twombly’s paintings often refer to myths about doomed lovers like Hero and Leander, Achilles and Patroclus. Twombly’s paintings about Hero and Leander are inspired by the poetry of Christopher Marlowe. Hero and Leander are separated by a narrow stretch of sea. Leander swims across the narrow sea at night to be with Hero. Hero shines a light from a tower to guide him. A storm interferes and Leander drowns. Upon seeing his body, Hero jumps to her death in the sea.

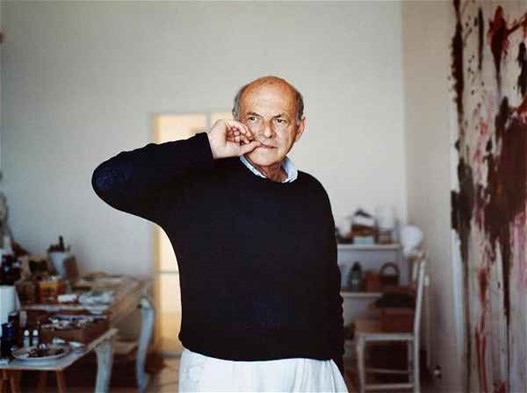

Several years after Twombly’s death in 2011, acclaimed photographer, Sally Mann, produced a book about Twombly’s studio in Virginia, called Remembered Light in 2016. It contains softly focussed photographic images sans Twombly. Twombly was her friend and mentor and every image suggests his presence. Mann photographed the light that poured into the studio and the reader’s consciousness. After seeing these photographs, suddenly I saw a lyrical and elegant artist engrossed in poetry, mythology and ancient history.

Mann said that Twombly’s art maintained a “wonderful balance between the sublime and the ridiculous.” An echo of the range of the work can be also understood in comments by Adrian Searle, chief art critic of The Guardian. He wrote after attending a Twombly exhibit in the Tate, “There are great Twomblys and terrible Twomblys, and the two are often the same. At his best, what inspires him – often a poem, a myth, a story or a place – is at one with what he makes of it.” (The Guardian, 17 June 2018).

Written by Luisa Blignaut.