A few years ago, I came across a Haitian art exhibition titled “Kafou: Haiti, Art and Vodou” (from 2012-2013) at Nottingham Contemporary, UK, and was instantly drawn to the strangeness of the imagery displayed. This month, we explore the unique and vibrant world of Haitian art.

“Vodou” (distinct from the practice of Voodoo dolls) is the syncretistic religion of Haiti that blends the beliefs of multiple West and Central African religions with Catholicism. It is also said to contain elements of Islam, European folklore, freemasonry as well as faith of the Taíno people indigenous to the Caribbean. A lot of Haitian art—with its unique stories and rituals—can appear quite incomprehensible without some knowledge of Vodou. The term “Vodou” derives from a word which means “spirit” or “god” in the Fon and Ewe languages of West Africa.

As for “kafou”—according to the text on Nottingham Contemporary—it “means ‘crossroads’ in the Haitian Creole language. Crossroads have great significance for Vodou, since they are the place where the world of the living and the world of the spirits meet. Kafou is himself one of the lwas, as the Vodou spirits are called.”

In my article on African masks, I explored how belief systems from the continent operate with the conviction that one can interact with the world of unseen entities. In Haiti, this feature takes on new layers of complexity as diasporic African faiths are mixed with different theologies, cosmologies, mythologies, and the local environment.

In the paintings above, Agoue is the lwa who rules over the ocean, the marine flora and fauna, and is also something of a patron saint to sailors and fisherfolk. Damballah, whose form is the serpent, is the lwa who is the primordial creator of the universe and all life. He is associated with the Christian figures Moses and St. Patrick. Although Damballah is the creator, he is not the supreme transcendent source of power—that position belongs to Bondye (from French Bon Dieu—“Good God”).

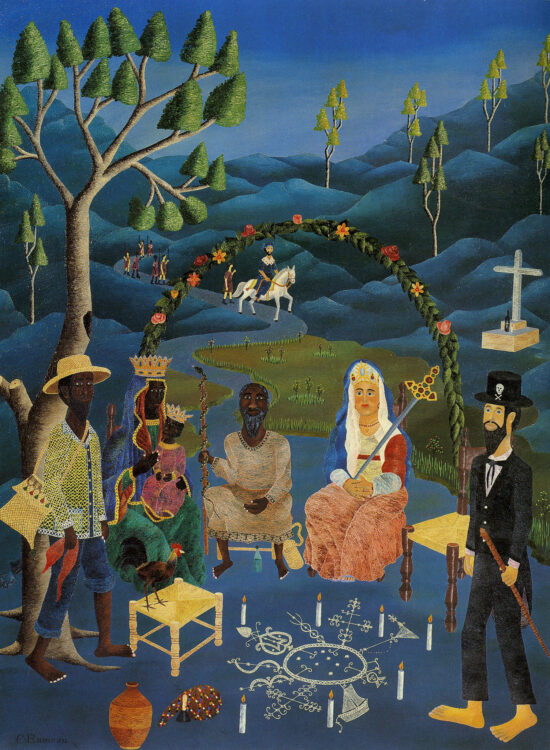

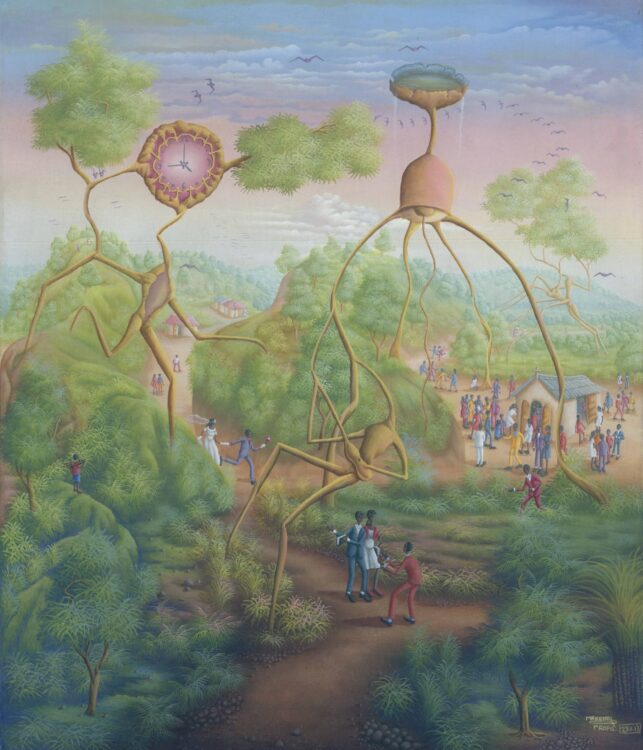

In this painting by artist Cameau Rameau, the most prominent figure is the one who resembles the Black Madonna. She is Erzulie—an intermediary lwa of benevolence between Bondye and believers.

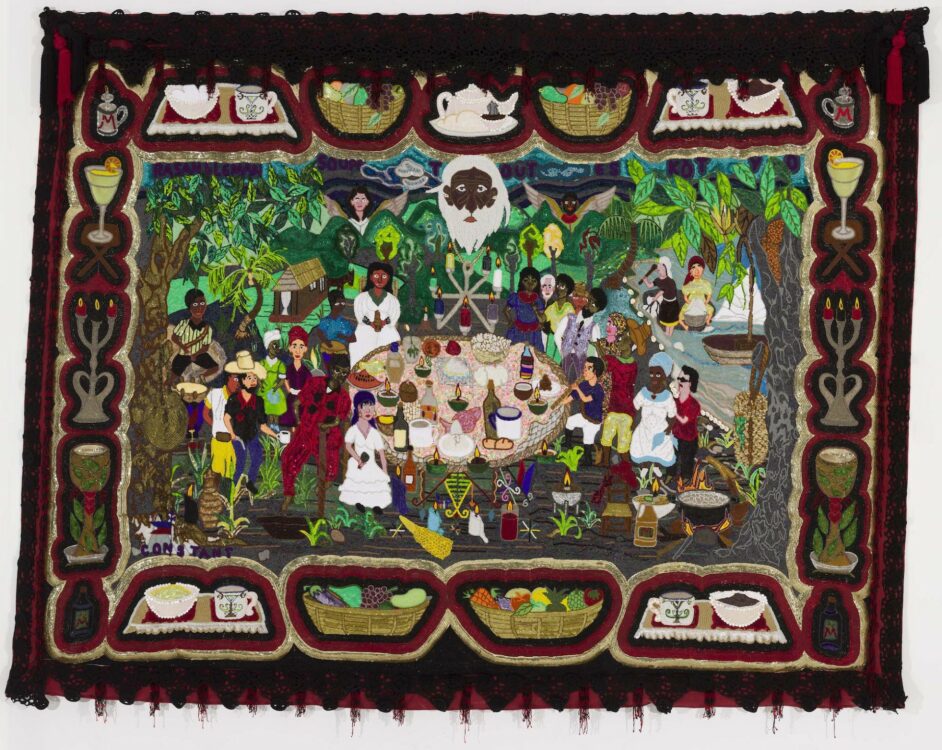

In addition to portrayals of entities that could be invoked and worshipped, Haitian art contains several scenes of ceremonies and gatherings. The tapestry “Rasanbleman Soupe Tout Eskot Yo” (All the Escort Gathering for Supper) by textile artist Myrlande Constant is a reimagination of The Last Supper from a Vodou perspective. The word “rasanbleman” in Haitian Creole, points out Haitian-American anthropologist Gina Athena Ulysse, means “assembly, compilation, enlisting, regrouping (of ideas, things, people, spirits)”. In Constant’s artwork we see the mixing and shuffling of humans, lwas and food, a disregard of fixed hierarchies and the emergence of fresh social dynamics.

Beyond Vodou mythology and ceremonies, I searched for Haitian art of a political nature—but references to it are quite limited online. A few sites talked about murals but I didn’t find the information substantial enough for study. Much of Haitian art is put under the “naïve” category, that is, it is created by artists with no formal training, with techniques and themes being simply passed on from generation to generation. (Some art commentators find this assessment to be unfair, saying it has damaged the overall reputation of Haitian art, and that it deserves greater recognition and appreciation internationally.)

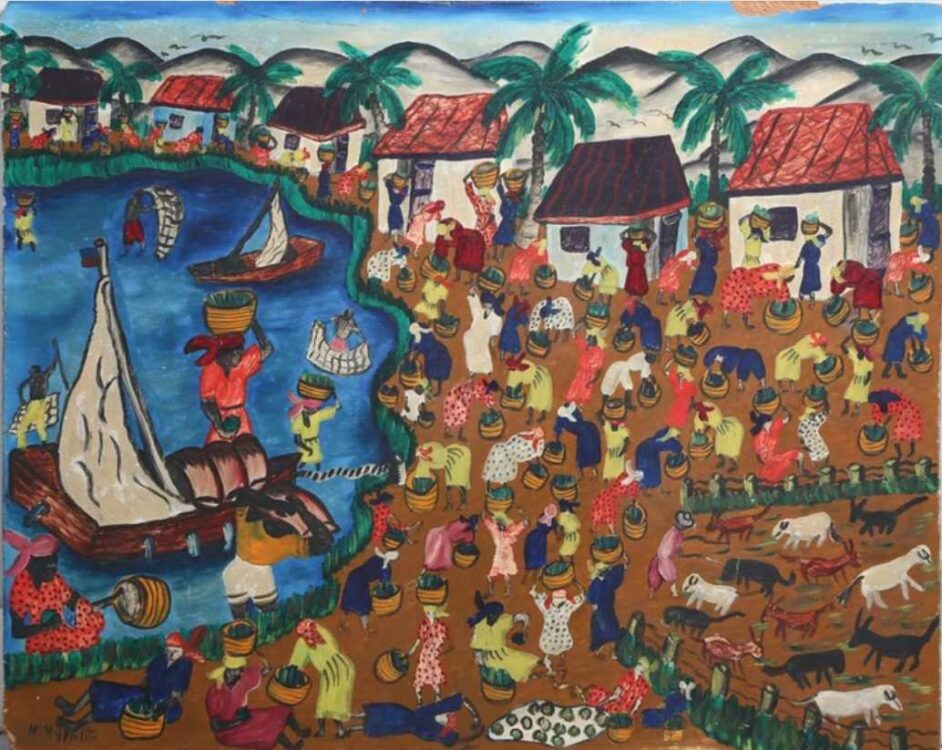

The “naïve” Haitian art that is easily accessible online usually contains depictions of everyday life, the sea, homes, people quietly engaged in their tasks.

Below is a landscape by Hector Hyppolite (1894–1948), called the “Grand Maître of Haitian Art” and “Timelessness” by Makenol Profil, (2013) (born 1979). The first shows humble seaside commerce and the second, active, synergistic communion with nature. One can discover countless works by different Haitian artists playing upon these subjects.

I believe this type of art that communicates the simplicity of rootedness and quotidian purpose—which may very often be deemed undramatic and overlooked—has its own very important role to play in the nation’s artistic corpus. It is the true sign of resistance from the people of a land which has suffered much during natural and manmade calamities.

Consider that instead of voicing shrillness, anger and bitterness in the wake of civil unrest, disaster and poverty, an overwhelming number of Haitian artists have the willpower to pick up the brush and create work that radiates peace, positivity and perseverance. There is tremendous beauty and power in that act, which is necessary for any culture.

To learn about more Haitian art check out Haitian Art Society, Indigo Arts, Ayiti Gallery, Myriam Nader Haitian Art Gallery and HaitianArt.com.

Written by Tulika Bahadur