Medieval European Artistic Objects

While swiftly going through Western art history in college, I found that different periods—ancient, medieval, Renaissance, modern and contemporary—made certain immediate and general impressions on me. Ancient was very much about sculpture (white, marble), Renaissance a mix of grand architecture and painting, modern and contemporary scenes went from figurative to abstract. As for medieval—it was highly geometric and intricate (with its Gothic cathedrals) and colourful and bright (with its illuminated manuscripts). Another noteworthy feature of medieval art, I noticed, was its unique “objects”. Many of them portable, ornate and religious. It makes sense that during an era of limited travel, little distraction and amplified piety people would need physical things in hand they could reflect upon.

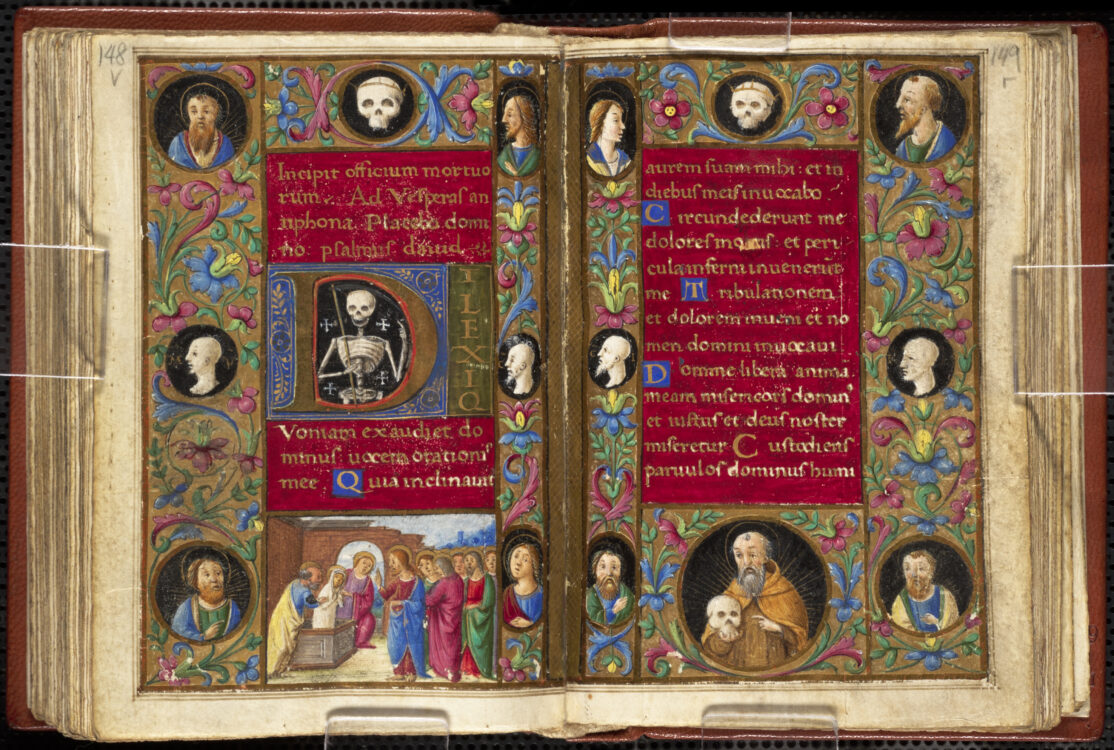

The term that comes up again and again in medieval art-historical texts is “the book of hours”. It was a book of private devotion laying out prayers for fixed times of the day—containing some of the most exquisite art of the period. Individualised for their patrons, these books depicted scenes from the Bible or lives of the saints in lush miniatures.

An essay on the Met, New York, calls the book of hours a “medieval bestseller”. Initially commissioned by members of the nobility, over time—with economic prosperity and the spread of literacy—they were demanded and could be afforded by ordinary citizens. Thousands of such books were made between 1250 and 1700 and are displayed today in libraries and museums.

Beyond the book of hours, one finds ivory carvings—these could be both religious and non-religious. Below is a four-panelled presentation of Christ’s suffering. Next, a mirror case with a couple. Mirror cases, which could fit in the palm of one’s hand, were a symbol of status. Most medieval carvings were coloured or gilded. Only faint traces of the surface layer remain in some artworks.

Another special artistic object from the Middle Ages is the chasse—or casket. Some of these boxes were reliquaries, that is, containers of relics. Caskets were designed in the shape of a church or a tomb. The vast majority had paintings of Christian personalities upon them. A few featured secular figures, for instance, troubadours (composers and performers), who can be found on a casket kept at the British Museum. Additionally, there were some “marriage caskets”, used during courtship. According to the entry on the Princeton Art Museum website, these were small keepsake boxes often used as gifts. In Italy, “when two families agreed on the terms for a marriage, the suitor would present his intended with a casket of jewels before he gave her a ring.”

Tapestries from the period stand out as well—many of which are allegorically rich and complex. The one that comes to my mind right away is “The Lady and the Unicorn”—a set of six—on display at the Musée de Cluny in Paris. Woven around 1500 in Flanders, the series is executed in the millefleurs (literally “thousand flowers”) style—which contains a background of numerous small flowers and plants.

All six tapestries have a noble lady with a lion and a unicorn, and some other characters. Five of the six are meditations on the senses—touch, taste, smell, hearing and sight—each implied by certain gestures. For instance, in “Taste” the lady is offered sweets by a maidservant. In “Smell”, she makes a wreath of flowers.

In the last tapestry, titled “À Mon Seul Désir” (translated both as “my only desire” and “my desire alone”), the lady is placing her necklace in a chest held by her maidservant. This scene has led to several interpretations. It is believed that, overall, it alludes to chivalry and courtly love.

If one spends time searching online, more interesting medieval European artistic objects emerge—altarpieces, chalices, chess pieces. When you study the thought, care and prowess behind many such creations, you realise that the Middle Ages (entire span from 5th to 15th century) were far from a period of stagnation or decline, as is believed by the masses. The term “Dark Ages”, serious scholars of history now say, accurately applies only to the period immediately after the fall of the Roman Empire—starting from the 5th to, at the most, 10th century. The rest of the Middle Ages remains active and alive. The positivity, ingenuity, inventiveness and dynamism of the era are unambiguously revealed in the art produced therein.

Written by Tulika Bahadur