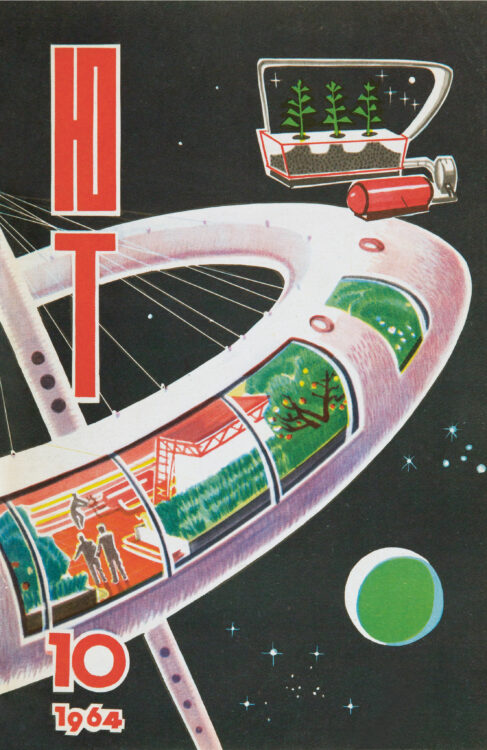

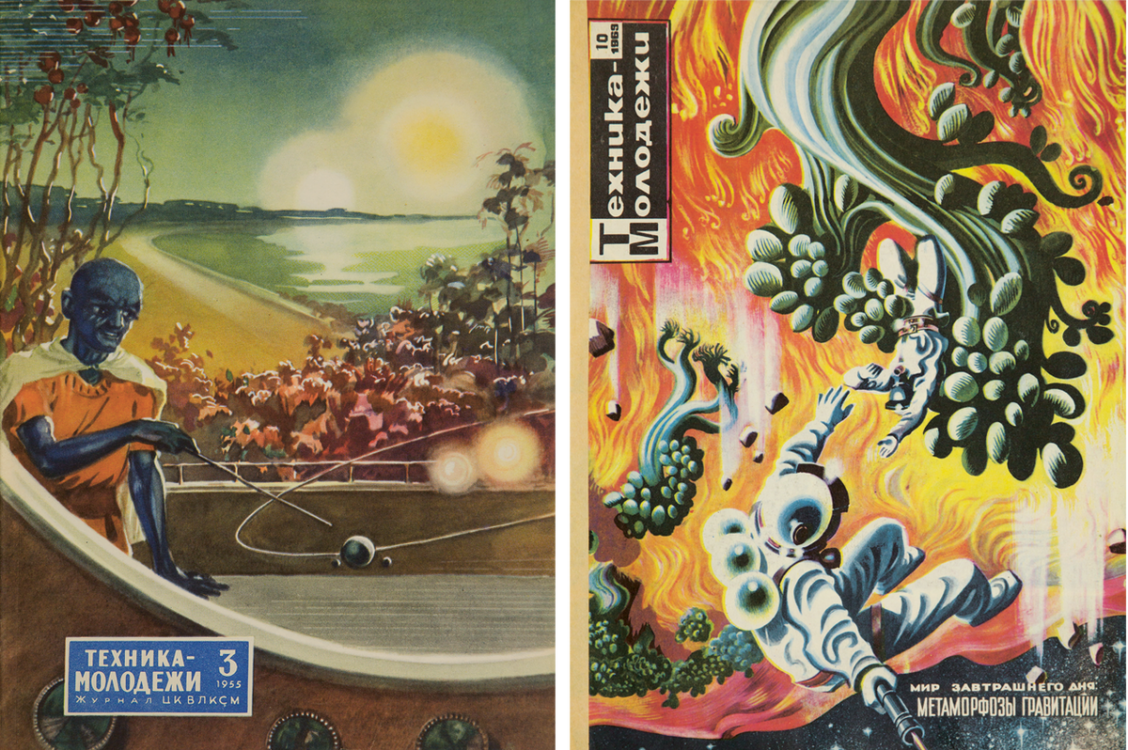

Many of us are aware of the Soviet Union’s space programme, and have probably heard the names of Yuri Gagarin, Valentina Tereshkova and Laika. A richly illustrated book of Soviet Sci-Fi Art, published by Phaidon titled Soviet Space Graphics: Cosmic Visions from the USSR (2020) presents 250 illustrations taken from popular science magazines of the space race period, depicting “daring discoveries, scientific innovations, futuristic visions, and extraterrestrial encounters”. At one point, there were 200 titles of these magazines in circulation. Out of these, a very prominent monthly that began in 1933—Tekhnika Molodezhi (Technology for the Youth)—is still active.

Curated by Alexandra Sankova—the director and founder of the Moscow Design Museum (established in 2012 with the mission to record, preserve and promote the design heritage of Russia)—the Phaidon collection features artworks created against a backdrop of geopolitical uncertainty and competition. The illustrations served multiple purposes—they were educational and entertaining for the masses, also a tool of propaganda for the state.

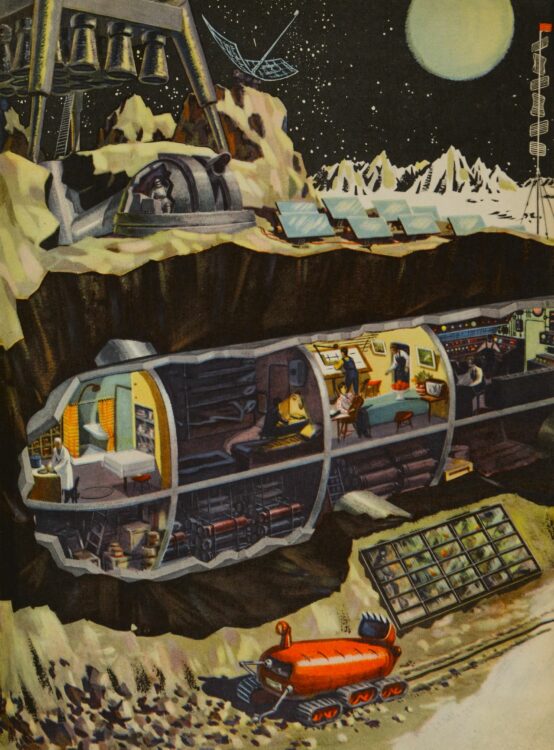

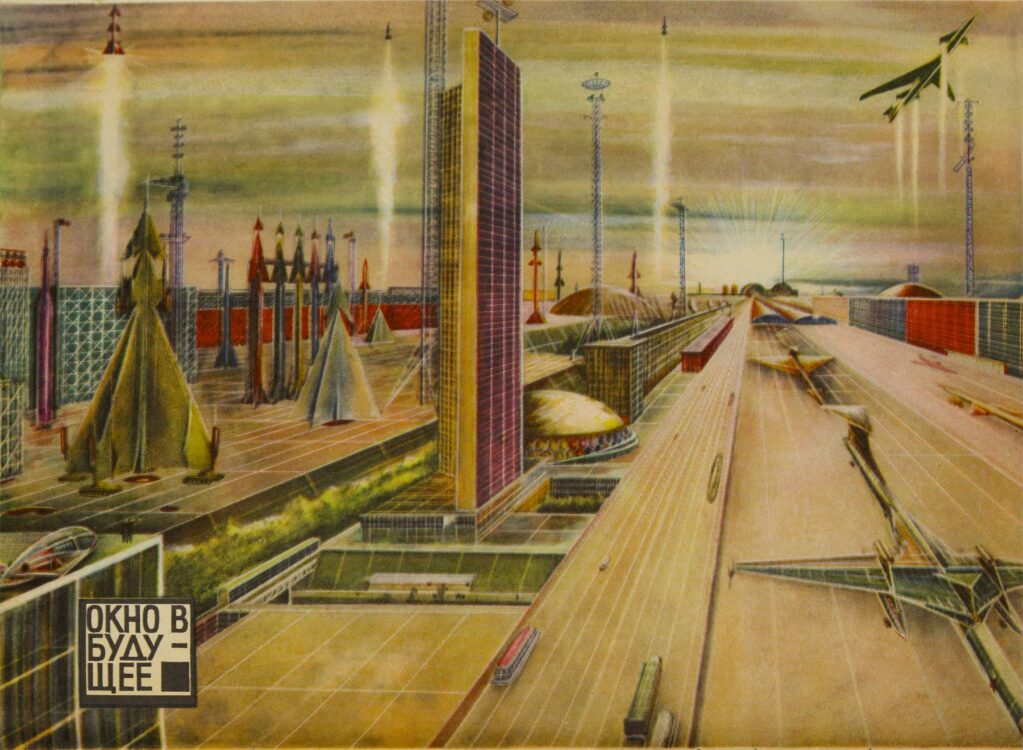

A quick glance through the collection will amaze and impress the viewer. Stylish astronauts and complex spacecrafts emerge right away. But beyond these, one can find interactions with alien life forms, attempts at energy generation, the carefully planned process of settlement in distant, difficult territories, advanced architecture, and much more—all of this executed with geometric precision and dramatic vividness. The images look like scenes you would see in a large cinema hall. We can easily ascertain that these projections are rooted in genuine technological progress and make the most of the science of the time.

It is fascinating how the graphics celebrate the thrill of exploration and move on to lay out possibilities of habitation (either within manmade spacecrafts or on other celestial bodies) in pictorial detail. We find the cultivation of vegetation, the construction of homes, inter-planetary transportation, also the practicalities of family life (with children and pets) and professional life (with office space and storage areas). Moreover, recreation.

Sankova writes that many artists of the period had technical formation. Art, philosophy and science had been a blend for a while. Ideas of travel between planets (and also entire universes) had been widespread, thanks to the works of personalities like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), who was a rocket scientist and pioneer of astronautics. An eccentric recluse, Tsiolkovsky spent most of his life in a log house near the city of Kaluga, 200 km southwest of Moscow. The site is home to Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics. The Space Age officially began with the launch of Sputnik I in 1957. Tsiolkovsky’s books had been in print since late 1800s, and, over the decades, had proposed concepts of space colonisation—of the Moon and farther parts of the Milky Way.

Furthermore, an event known as the “Khrushchev Thaw” (mid-1950s to mid-1960s) is greatly reflected in the content and design of the space illustrations. Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971), who was First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, introduced policies of de-Stalinisation and peaceful co-existence with other nations (except perhaps rival superpower United States). Also, censorship was significantly relaxed in media and the arts. One can clearly notice these developments taking visual shape and form in the graphics. The presence of bright colours indicates confidence and positivity. There is also a lack of conflict, violence and disaster. The habitation of other places is shown as, although intellectually and physically demanding, an overall smooth experience. New territories are not inhospitable. Societies can be established on them without friction at every step.

What is so noteworthy about the images is that even if you know little about the political backdrop, the phenomena in them will make sense to you. Sankova writes that the topics which the illustrations explore continue to be pertinent: “The interest in it [the Soviet view of space] is returning, or it’s more correct to say that the interest has never faded. The topics popular in the 1960s and 1980s are now relevant again—ecology, alternative energy, reasonable consumption, overpopulation, and waste recycling. Back then it was regarded as futurology, but for us it’s already the reality.”

The illustrations are a sheer delight for the fun and inventive way in which they bring to life and disseminate serious scientific topics—that would remain incomprehensible if limited to abstruse academic journals.

Images from “Soviet Space Graphics: Cosmic Visions from the USSR” (2020)

Written by Tulika Bahadur