If you’ve taken a business class in school or college, chances are you have given some thought to why people consume (any product or service), how they behave while making a decision to purchase something, and how their needs must be identified and fulfilled.

Art, unfortunately, is one realm where the aforementioned issues aren’t sufficiently considered—and they are engaged with passionately in just every other industry! I see, at the heart of the creative sector, too much negativity—gallerists, curators, museum directors, journalists, artists themselves blaming “people” for not being interested. And every day I have less and less sympathy for these complaints. Because a “transaction” can only occur when the affordability and requirement of one party is catered to by the skills and deliverability of another. If a 40-something man with two growing children walks into an art gallery and finds the starting price to be $10,000 or a single female in her late 20s yet to achieve financial stability is told that paintings and sculptures begin at $5,000, you cannot really point fingers at the individuals here if there are no sales.

It is the art establishment (with all its practitioners) that ought to be more open, more responsive to the rest of the world. It is a common idea that genuine creative talent and commercial viability may not be aligned—for all sorts of reasons (the masses aren’t cultivated enough to appreciate real art, artists cannot become marketers and salespeople, and so on). These are misconceptions because there are far too many examples of highly gifted artists who have been able to successfully convert audiences into buyers while preserving their own essences and expressions.

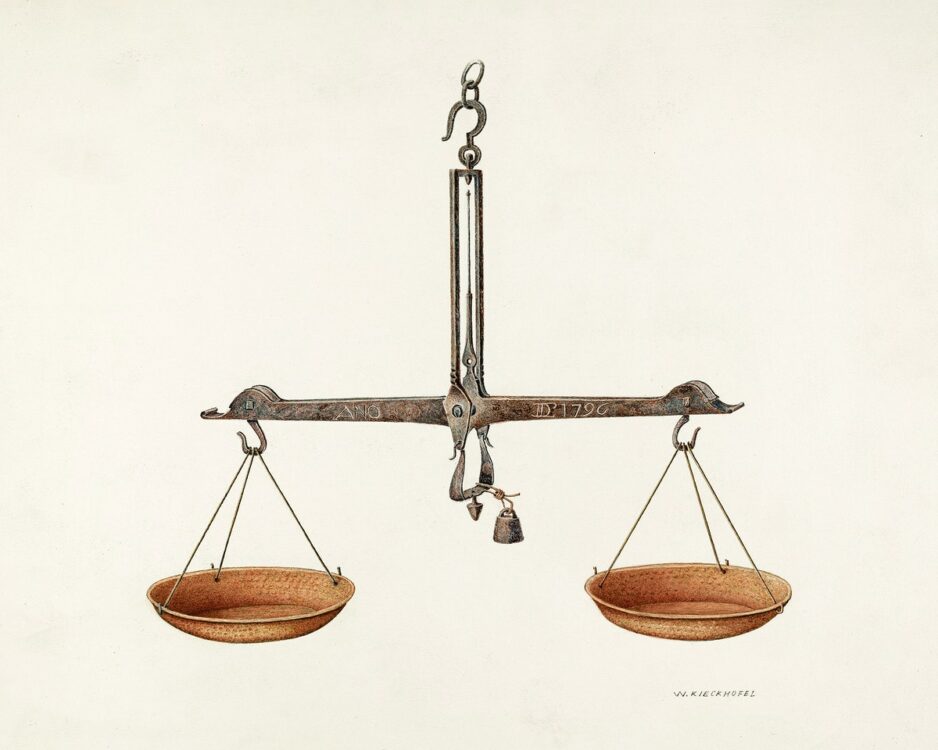

Here are some ways in which an artist could strike the balance:

1). Understanding the Place of Art within a Larger Economy

The very first step, in my opinion, is a psychological one. Any creative person must understand that the item they intend to produce and sell exists within a highly competitive marketplace of several items, that the target audience has limited financial resources, and must choose judiciously. Even individuals with a considerable discretionary income will think long and hard before buying art. Why put $10,000 in a single painting the emotional or intellectual pull of which will most likely wear off after a while and which might be a tough resell? Why not use the same money to travel overseas and create precious memories that will last a lifetime?

The point is by training oneself to empathise with the target consumer, stepping into their shoes, evaluating situations from their perspective, a creative person will be more practical in their approach to their career. Penetrating the consumer mindset will make one more flexible (which they must remain without turning formless) and capable of evolving when necessary (which they must without dissolving the core of their identity).

2). Creating a Range of Offerings for Different Budgets

The natural subsequent step is to meet people at the level they are at, that is, to produce a variety of things with different price tags. Curious individuals who make an enquiry mustn’t feel that there’s nothing for them to buy. Why should anybody be allowed to leave empty handed? Somebody who’d have $10,000 ready is always welcome. But something must be available for those who have only $50 as well.

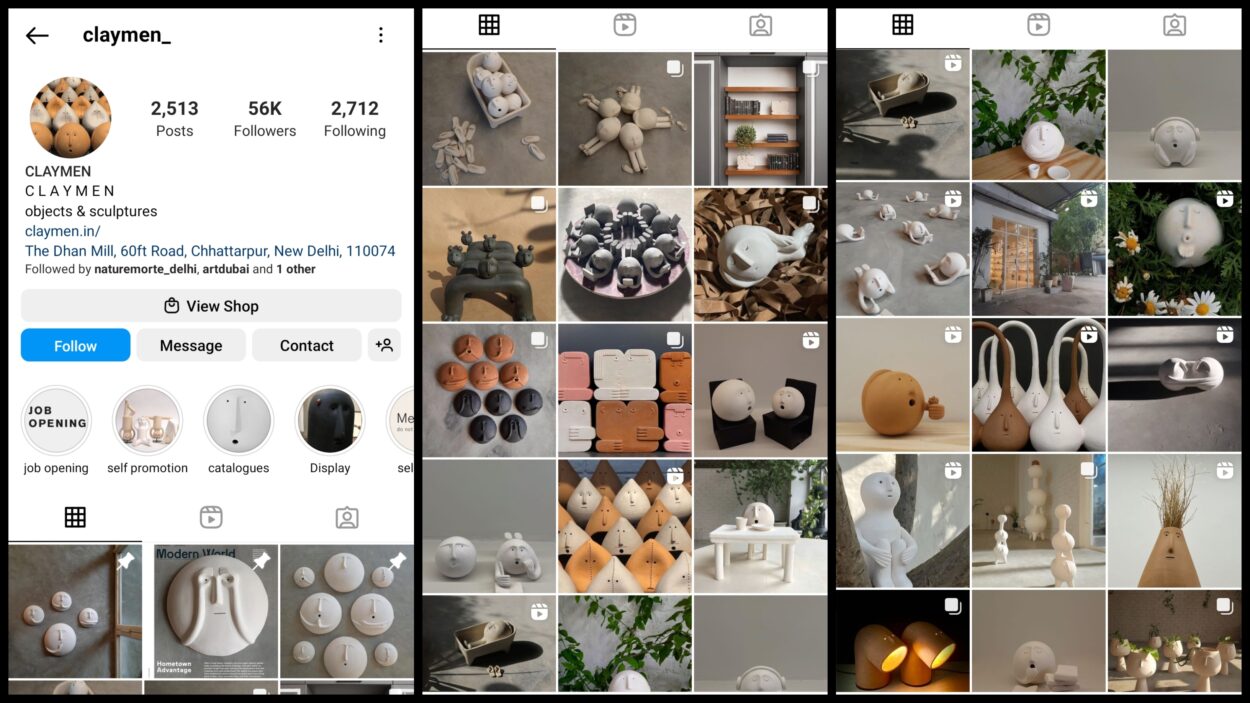

3). Mixing Fine with Applied Art

Next, as I have mentioned in a previous article, merging art with a functional object or experience is a great way to expand one’s market. A lot of people may simply not see any value in purchasing paintings or sculptures but can entertain the idea of acquiring art if it is impressed on something they can use—apparel, furniture, home décor, notebooks, the list is endless.

An appropriate example for both the points above is the Indian sculptor Aman Khanna who has created a brand named “Claymen”. These are stripped down and, consequently, magnified human expressions with immediate universal appeal. Khanna has a considerable following on Instagram (@claymen_) and sells his Claymen in forms that could be large sculptures (purely decorative) or small accessory holders or vases (functional pieces) or anything in the middle (large pieces can be functional too, and smaller ones purely decorative). He is also able to attract a variety of buyers because of his price range. The functional objects do not diminish his creativity or reduce his status as an artist, rather they help generate more mass appeal for him.

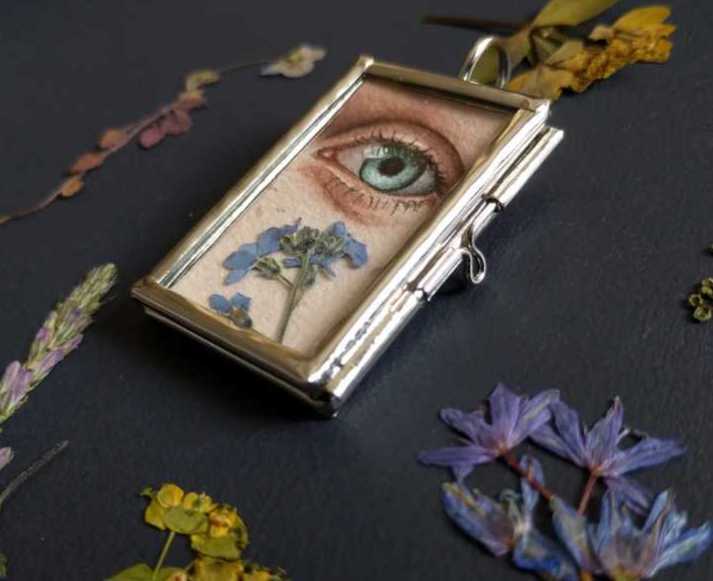

4). Being Proactively Bespoke

Lastly, having an artistic practice that is more bespoke can help attract more consumers. Most artists are happy to take commissions after they have made pieces of their own choice. But flipping this dynamic may also work very well for quite a few, if not for everybody.

A good example is that of contemporary imitations of the historical “Lover’s Eye” (miniature portraits of one’s beloved on rings, brooches, pendants, etc.).

On Etsy, there are several skilled portrait painters who offer custom-made antique-style jewellery with the lover’s eye. This way they are able to both satisfy the specificity of consumer need and get an opportunity to display their talent. Such a customised artistic practice may involve any value proposition: pet portraits, baby portraits, joyful childhood memories, dreams, whatever the artist can come up with after letting their own capabilities intersect with the lived experiences of others.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.