A part of history and geography that I find quite “unknown” is the Pre-Columbian world. The fact that we call it “Pre-Columbian” itself indicates how obscure it remains in our imagination. It is said that it was the year 1498 when Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) reached mainland South America, specifically the Paria Peninsula in present-day Venezuela. Thinking it an island, he christened it Isla Santa and claimed it for Spain. The eras and cultures that lie behind this marker may conjure all manner of images and ideas.

I think of gods and goddesses with unpronounceable names, violent rituals, pyramids, gigantic sculptures of heads, astrology, prophecies, lots of stone. Three words are immediately recalled: “Maya”, “Aztec”, “Inca”. And how does “Mesoamerican” fit in? Just how many civilisations existed before 1498 and on what timelines—this information is beyond most of us.

I gained some awareness of this indigenous world that flourished prior to European colonisation while browsing through books on world art history. But my true interest was piqued only recently when I stumbled upon an article on the online magazine Aeon (https://aeon.co/essays/aztec-moral-philosophy-didnt-expect-anyone-to-be-a-saint) titled “Life on the slippery Earth”, with the introduction: “Aztec moral philosophy has profound differences from the Greek tradition, not least its acceptance that nobody is perfect.” This write-up immediately brought the obscure world a little closer, making it more comprehensible, opening up its internal richness. I began to look at Pre-Columbian art with a more curious and engaged gaze.

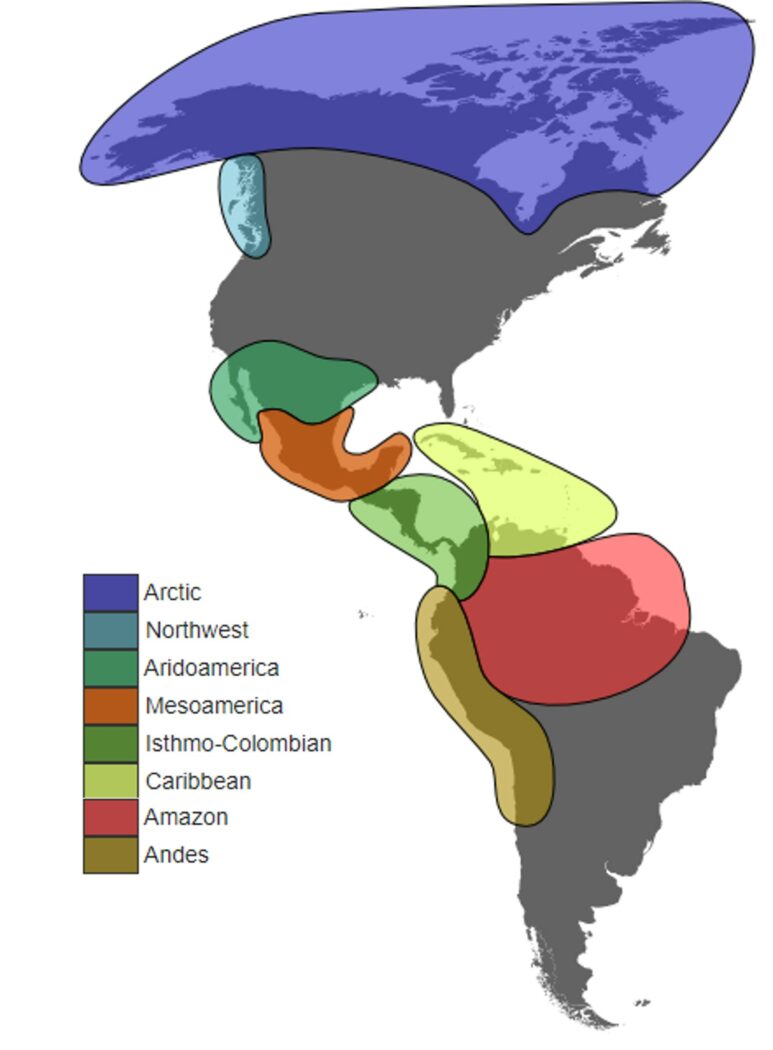

The image below will give some context.

Here I have selected five pieces to convey the diversity and depth of Pre-Columbian cultures.

1). The Aztec Sun Stone

The first one is the Aztec Sun Stone located at the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City. The Aztecs lived in central Mexico from 1325–1521 AD. This intricate stone is believed to have been carved between 1502 and 1520 by the Mexica people, who were rulers of the Aztec Empire. Almost 25,000 kg in weight, it is 356 cm in diameter and 99 cm in thickness.

At the centre of the disk is the solar deity Tōnatiuh. The surrounding rings contain images of animals (like crocodile, monkey), natural phenomena and elements (grass, wind, earthquake and rain). Certain symbols stand for previous eras. The shape and structure of the sculpture is also a reference to the city-state Tenochtitlan. The artwork is a calendar, an object of worship, a political statement, much more. Interestingly, it continues to be an important subject of academic research with newer interpretations added now and then. What I find interesting about the piece is that it represents a population’s passionate desire to situate itself within a complex and coherent cosmology and mythology, to strive for order and meaning.

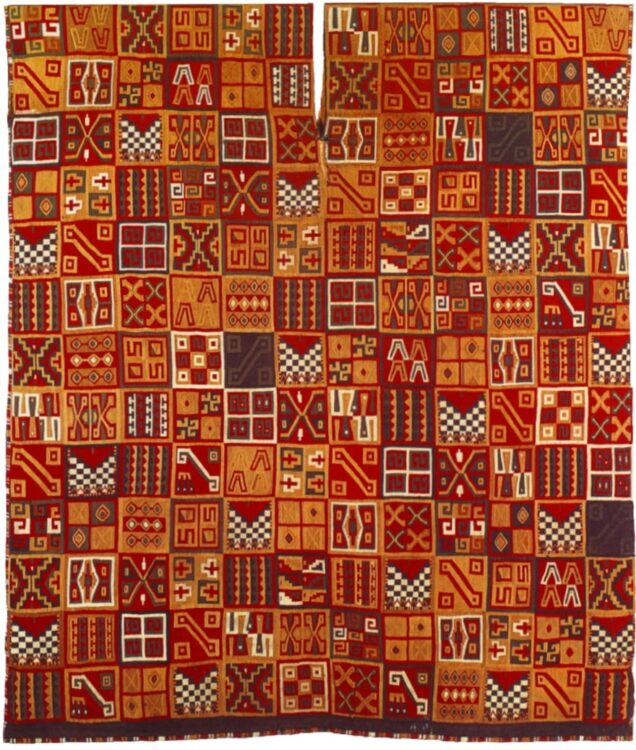

2). Inca Textiles

The Andean region is known for its rich production of textiles. The Inca Empire—which arose from a pastoral tribe in the 12th century and continued till the 1500s—is especially famous for its garments. The patterns are often geometric and, it has been discovered, “ideographic” in nature. They are codes representing social and political status, also clan identities. In addition, textiles were used as taxes and means of payment. What makes these fabrics and designs noteworthy is the way they bestowed multi-purpose functionality onto a simple item.

3). Olmec Colossal Heads

Mesoamerican like the Aztecs by region but much older (c. 1,600 – 350 BC), the Olmecs were preoccupied with celebrating their authority figures. They lived on the Gulf of Mexico, in the tropical lowlands of present-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco. Their large heads—portraits of their rulers, frequently adorned with headdresses—were sculpted out of basalt and stood between 1 and 4 metres, weighing anywhere between 6 and 50 tons. While many cultures make busts of kings and emperors, the Olmec heads remain distinctive because of their scale, and consequently, the power they exude.

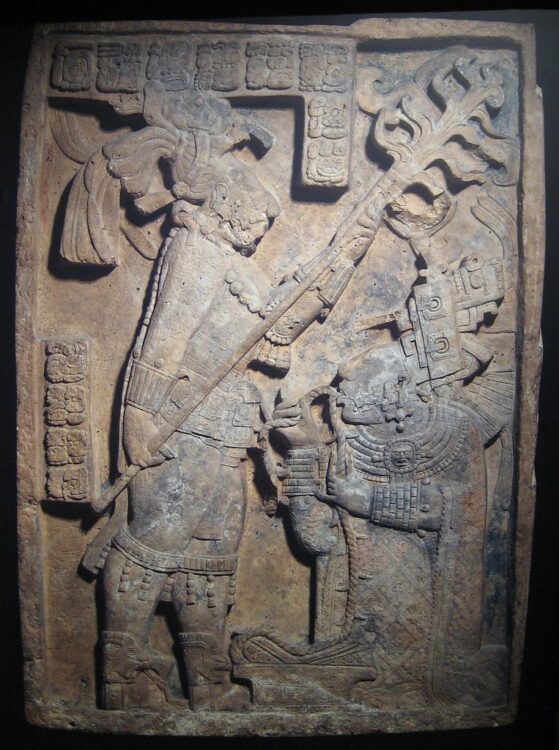

4). Mayan Lintels

The Mayan civilisation—which was at its height between the years 250 and 900 AD—erected buildings with elaborate decorations. The carved stone lintels particularly above their doorways carry important scenes. Structures in the ancient city of Yaxchilán, in the state of Chiapas in Mexico, display reliefs with various activities.

The relief from the Yaxchilán lintel above, now at the British Museum, depicts a “blood-letting” ritual featuring the king of Yaxchilán, Shield Jaguar the Great (681-742), and his wife, Lady K’ab’al Xook (also known as Itzamnaaj Bahlen III). The Mayan élite drew blood from various parts of their bodies, a ritual performed to establish communication with gods and spirits. The blood-letting relief, which modern viewers might find disturbing, is at once personal and social, giving valuable insight into general Mayan culture via a delicate act of negotiation within a relationship.

5). The Nazca Lines

Lastly, moving to Peru we find the Nazca culture (which flourished from 100 BC to 800 AD) in the southern part of the country. They were skilled at several crafts but their most prominent artistic achievement is a group of geoglyphs—giant designs etched into the land—created between 500 BC and 500 AD, preserved till today owing to the stable climate of the region.

Named “the Nazca Lines”, these massive drawings cover an area of 50 square kilometres. Some are simple geometric shapes, others forms of animals like spider and condor. There are also some plants and a human. The drawings can be viewed from airplanes and satellites. There are many theories regarding their purpose: they correspond to constellations in the sky, they are an irrigation system, they are ceremonial sites to appease the gods for much-needed rain, even alien involvement. They remain one of indigenous America’s big mysteries.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.