As my entrepreneurial journey progresses and life gets busier by the day—with more connections, conversations, proposals and plans—I find myself in greater need of energy. Yes, definitely greater energy for physical stamina—obtained via proper diet and suitable exercise. But more than that I require nourishment for the immaterial part of me. Procuring and assimilating this, I have realised, is more challenging than ensuring the fitness of the body.

The need for the right psychological/emotional/spiritual (whatever one might call it) fuel has made me very interested in the concept of “myth”. Myth is a tricky word. In common parlance, one may use it to suggest something fabricated or misleading that must be debunked (example, “five myths about the banking industry”). In a more academic sense, it may represent something antiquated and naïve—pre-scientific divinisation of natural elements and human pursuits (like “Egyptian” or “Norse”)—not very useful for the contemporary world.

I look at “myth” (and the collection of myths—that is, mythology) in a broad sense. I derive meaning from its Greek etymological root “mŷthos”, which can be “utterance, speech, discourse, tale, narrative, fiction, legend”. So myth for me is a big yet simple word. It is “story”—of any kind. Religious, philosophical, literary, political. It can be civilisational, public, individual, private. By default, it is not true or false, harmful or healthy. It is powerful and determines how we organise and fill up our cultures, our art, our existence, everything.

At this stage of life, I am interested in accumulating the very best myths for myself with a sense of discernment—and meditating upon them. I want these narratives—with the symbolism, imagery and lessons therein—to keep alive the flame of motivation within me day in and day out. I also feel my drive to seek these myths emerges from a desire to have a permanent source of power, one that exists outside of time and space, and, therefore, is accessible and can be tapped into anywhere at any moment.

There are various narratives that I have engaged with afresh up till this point. For instance, although raised a Catholic, I now look at the Resurrection of Christ in a completely different light. It is no longer just a festival to be celebrated once a year. Rather new birth is a phenomenon that must be actively pursued every day, where certain things in us must die and others given life.

Also, in spite of being an Indian and having always been surrounded by images of Hindu goddesses, I never really paid these archetypes much attention. It is only my current frame of mind that can understand their true meaning and value. One goddess who stands out is the ferocious Kali—representing power, time, and both destruction and creation. The pinnacle of ancient feminism, she takes charge when male deities fail to deal with the forces of evil. I heard somebody say awhile back that when the fiery aspect of the feminine is repressed, women run the risk of turning into fragile and plastic “Barbie dolls”. Kali is a representation of the primal impassioned core existing in every female, which must not be denied or ignored or subdued. In her frightening intensity and gruesome appearance, she is an expression of tremendous (self-liberating, self-empowering) ownership, of agency and independence, which is why I find her so awe-inspiring. These are all qualities that I must embody at all times if I want to achieve something substantial.

Beyond religion, from the world of literature, I have been giving thought to what, from a scholarly point of view, is known as “the hero’s journey”.

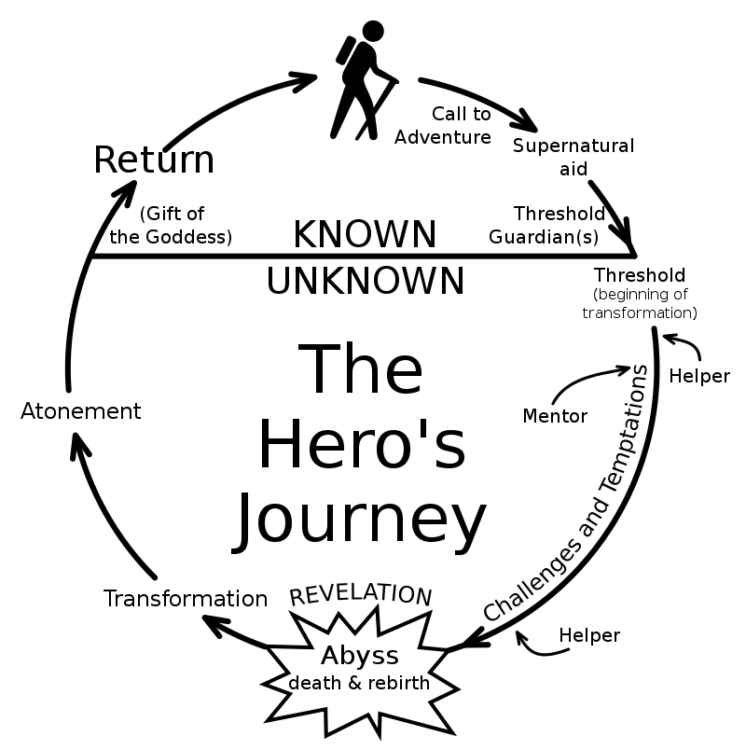

Found all over the world in different forms, this template lays out the basic structure of an adventure, wherein there are two worlds—an ordinary, known one and a special, unknown one. The hero feels a “call”, which he or she may resist. Eventual acceptance of the call is possible with the help of a guiding force or mentor. Challenges lead to a revelation, which leads to transformation, and consequently, the final accomplishment of a mission.

Interestingly, the template applies to any endeavour that is worthwhile. The importance of mentors is a need for which I feel strongly as I work on projects. These mentors may not be near me or may not know me at all. They may be figures whom I follow on Instagram or YouTube, who are able to transfer their vigour to me via their enlightening insights and practical tips. It makes me think—good, useful conduct is achieved more by the immediate imitation of other real human beings (who are more evolved than you in certain respects) than by contemplation of abstract theories of right and wrong.

The most exciting aspect of this quest for my personal mythology is the constant “translation” of the narratives that I choose into my concrete outward reality. And this makes me better understand why we have been so attached to myths all along. What we feed ourselves has a direct effect on us—it can diminish and degenerate us or build us up, make us radiate and actualise our potential. Everybody, especially those associated with creativity, must remember this at all times.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.