Going through the Instagram feed (@larryslist) of “Larry’s List”–the Hong Kong-based art market knowledge company providing insights, data and access to contemporary art collectors—I have been thinking a lot about the act of collecting, what drives it, what does it provide to the collector. The homes featured on Larry’s List belong to wealthy overachievers in various industries—from fashion designing to steel manufacturing. The rooms are carefully curated, with paintings and sculptures from renowned artists placed in living and dining areas.

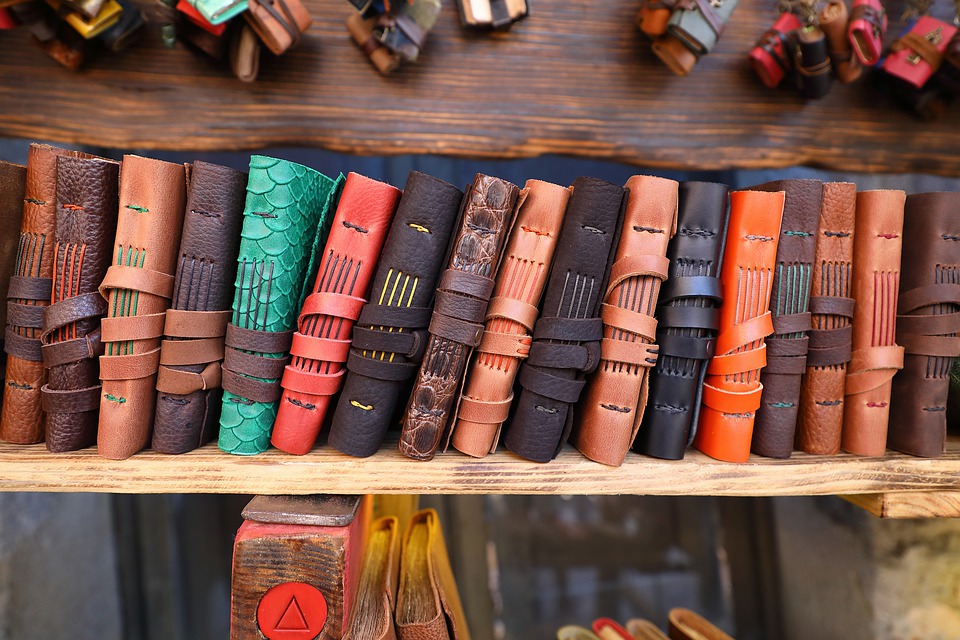

I’m curious about collecting and collections in general—whether it involves art, matchboxes, stamps, bottle caps, anything. I feel the impulse to collect most strongly for my journals and notebooks, versions of which I have maintained since the age of ten. I am amazed by the quiet and unprotesting ability of these inanimate items to bear the weight of human thought and emotion. Folded and tucked away in their pages, I find the air of different rooms, neighbourhoods, cities, countries, entire continents. I have stored all of them with a lot of affection and reverence—they contain my first attempts at creative writing, notes from a very important time when I subjected myself to the gruelling adventure of reading some of the greatest books ever written and watching the grandest films ever made and studying up the most significant movements in art. The pages contain reflections on life and the cosmos. Later, the exciting madness of entrepreneurship. These journals and notebooks are my own creations, and, therefore, extensions of my being. I find it impossible to part with them.

Why does the enterprise of collecting something—either constructed by oneself or by others—fascinate some of us so much? When you start looking for explanations online, a quick reference is Freud. Those adhering to his line of thinking believe that life, for many people—at least at a subconscious level—can seem chaotic and terrifying. The practice of collecting things gives a human being a feeling of agency and control. It is a way of imposing order over reality, and reducing stress and anxiety.

Related to the above motivation of imposing order is the tendency to establish continuity between the past and the present. Collectors driven by this impulse find themselves attracted to visions or objects that evoke nostalgia, that remind them of important events in the years gone by (for instance, floppy disks, painting showing the room of a college student). Or they may be drawn to antiques belonging to ancestors or prominent historical figures. The continuity could also be established between the present and the future, as in, a collection could be curated with the intention of leaving something of value for the next generation.

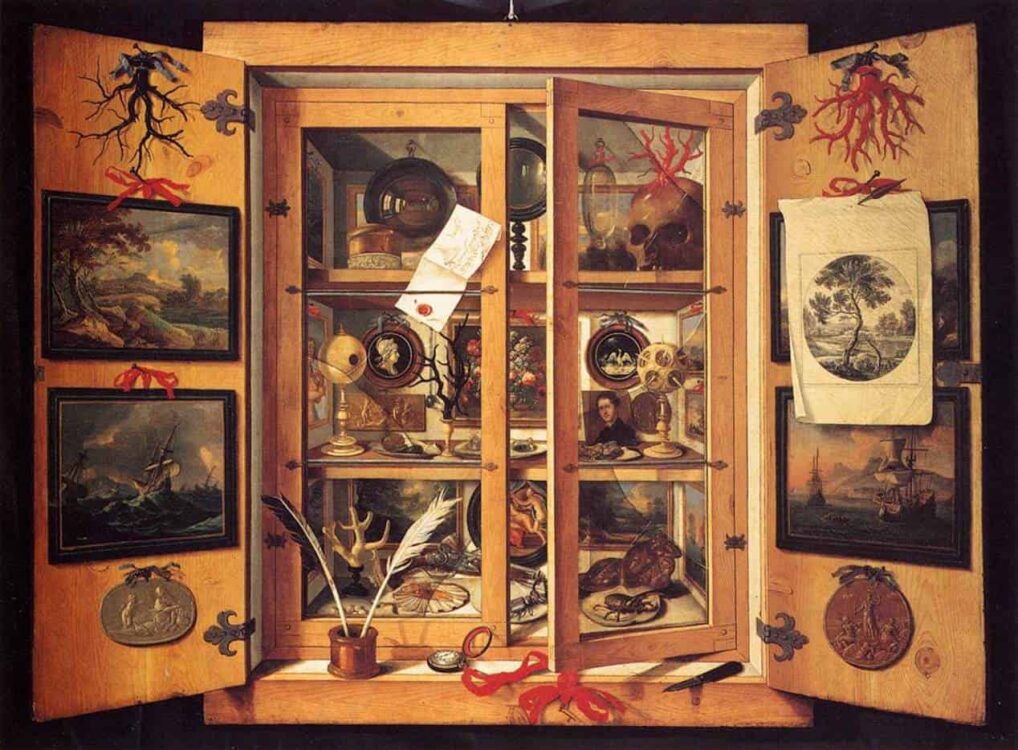

If familiarity is a stimulus behind collecting, so is foreignness. Things that are different, unknown, strange, exotic—discoveries of science or culture may be sought by collectors who are keen on better understanding the world beyond one’s zone of acquaintance. Such a practice is best known via the phenomenon of “cabinets of curiosities”, the earliest examples of which could be found in 16th-century Italy.

Another reason which is quite often mentioned in discussions of the psychology of collecting is our hunter-gatherer instinct. Even today we experience the thrill of the hunt very powerfully when encountering something rare and significant. Novelty is a trait that lights up the reward centre of the brain, and this experience can be addictive—leading to anticipation of similar exhilaration at some point soon.

Strongly commercial motivations behind collecting exist as well (whetted by our consumerist societies). Here the collection is a vehicle through which the brand identity of the collector is communicated and reinforced (and the items being treated as investments that could be sold off at a later date at a profit is a likely option).

Whatever the impetus, a personal collection is a haven of emotional attachment and intellectual stimulation for the collector. It is a place of safety, meaning, and most of all, passion and intimate engagement. This point is highlighted well in the book Cultures of Collecting (1994) edited by John Elsner and Roger Cardinal:

“While the museum is associated primarily with the public and the state, and with a condition of permanence, collecting—which provides its contents—is usually understood as a private and impassioned pursuit. The museum expresses a detached mastery over the objects and fields of knowledge that constitute its strengths; the collector, who may become the museum’s donor, has a personal preoccupation…The institutionalised collection stands as a detemporalised end-product, as an array of works abstracted from the circuits of exchange; the collector, on the other hand, is situated in the highly contingent time of market or non-market exchange…”

Written by Tulika Bahadur.