“Alchemy” is a term I first discovered as a teenager via the bestselling novel The Alchemist (1988) by Brazilian author Paulo Coelho. The book itself, a mystical fable about following one’s dreams, doesn’t quite explain the phenomenon, just alludes to it. References to the practice—which is an attempt to turn base metals such as lead or copper into nobler ones like silver or gold, and creating panaceas and elixirs—could be found across cultures and periods: Hellenistic Egypt, ancient India and China, the Islamic world and medieval Europe. Wikipedia calls it an “ancient branch of natural philosophy”.

Today, some dismiss alchemy as a naïve pseudoscience. Others find it more ambitious and adventurous, and consider it a “protoscientific” tradition, even the ancestor of modern chemistry. Over the years, I have found that alchemy has been a big topic in Western art. My interest in its portrayals has less to do with the chemical impossibility or possibility of it (its practical, knowable “exoteric” side) and more with its philosophical, psychological, metaphorical and spiritual significance, and what it might tell us about human desire and need (its mysterious and poetic “esoteric” aspect).

Visual representations of alchemy in the West span from antiquity to the Industrial Age. According to an exhibition on the subject at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles from 2016-17, alchemists sought “to transform and bend nature to the will of an industrious human imagination” and were keen on finding “the key to unlocking the secrets of creation”.

The alchemical worldview has been substantially shaped by ancient Greek philosophy and cosmology. Over time, it has picked up (and continues to do so) influences from a whole host of cultural and spiritual movements, anything from 17th-century Rosicrucianism to 20th-century New Age. The legendary Hermes Trismegistus (a combination of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth)—known to possess special wisdom on the relationship between material and spiritual realities—is a pivotal figure of alchemical mythology.

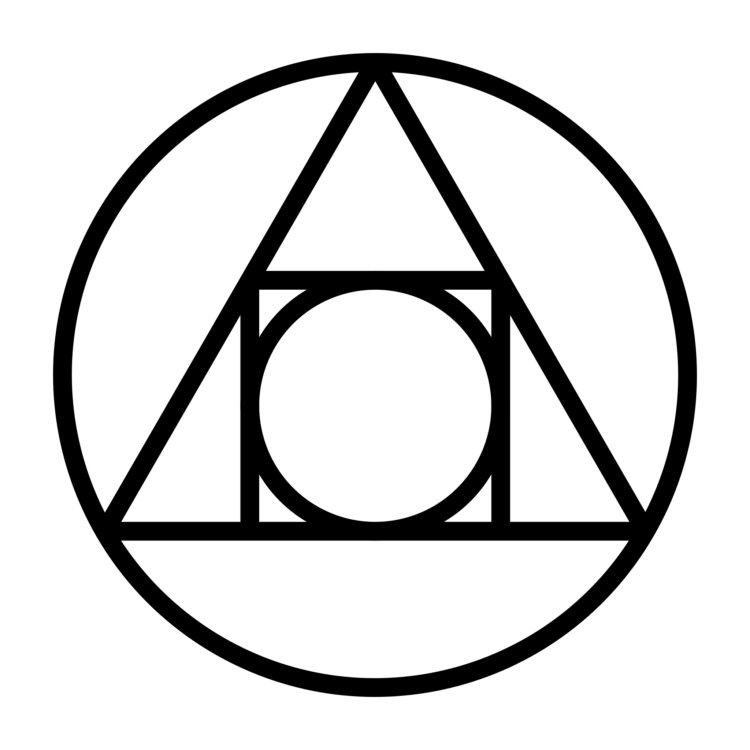

To understand the visual art on alchemy, one needs to get familiar with the theory behind its “process”, the stages involved, also known as magnum opus (great work). Its four main phases are used to describe the transmutation of prima materia (starting substance, a formless base like primitive chaos) into the mythical philosopher’s stone, the elixir of life that bestows immortality, the chief goal of alchemy.

The four stages go back to the first century. They are: (1) nigredo, the blackening or melanosis, (2) albedo, the whitening or leucosis, (3) citrinitas, the yellowing or xanthosis and (4) rubedo, the reddening, purpling, or iosis. All of these have meanings that transcend the laboratory. The chemical and physical states correspond to spiritual/psychological ones. Blackening is the dark night of the soul, whitening the washing away of impurities, yellowing the dawning of solar light or awakening, and reddening is wholeness of the self or successful vitality.

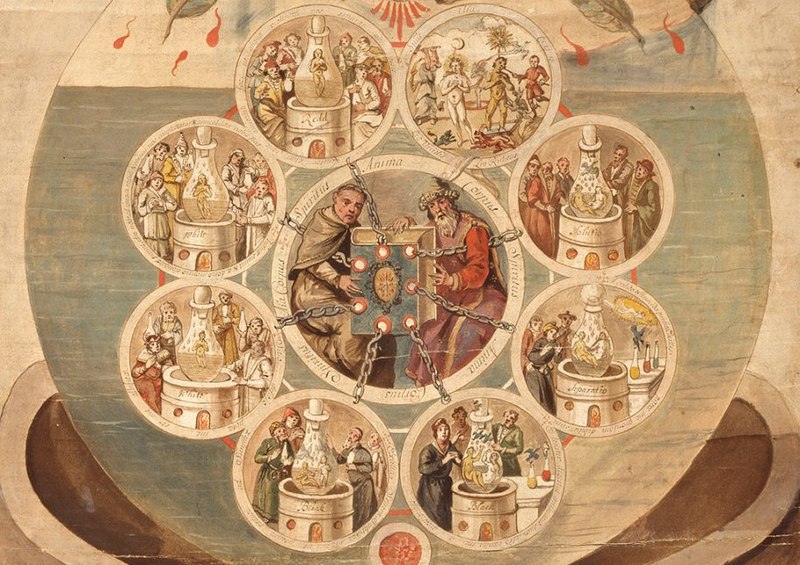

These four stages were expanded into 12 by English Augustinian priest George Ripley (c. 1415–1490): 1. Calcination, 2. Solution (or Dissolution), 3. Separation, 4. Conjunction, 5. Putrefaction, 6. Congelation, 7. Cibation, 8. Sublimation, 9. Fermentation, 10. Exaltation, 11. Multiplication and 12. Projection. English alchemist Samuel Norton (1548–1621) gives 14 steps: 1. Purgation, 2. Sublimation, 3. Calcination, 4. Exuberation, 5. Fixation, 6. Solution, 7. Separation, 8. Conjunction, 9. Putrefaction in sulphur, 10. Solution of bodily sulphur, 11. Solution of sulphur of white light, 12. Fermentation in elixir, 13. Multiplication in virtue and 14. Multiplication in quantity.

In art, various alchemical stages have been represented by different symbols over the centuries: animals, celestial bodies, human activities, scientific equipment. Here are two interesting artworks on alchemy…

- Splendor Solis

Central to alchemical lore are death and rebirth. The old king must die for the young one to take his place just as base material must be destroyed to initiate the production of the philosopher’s stone.

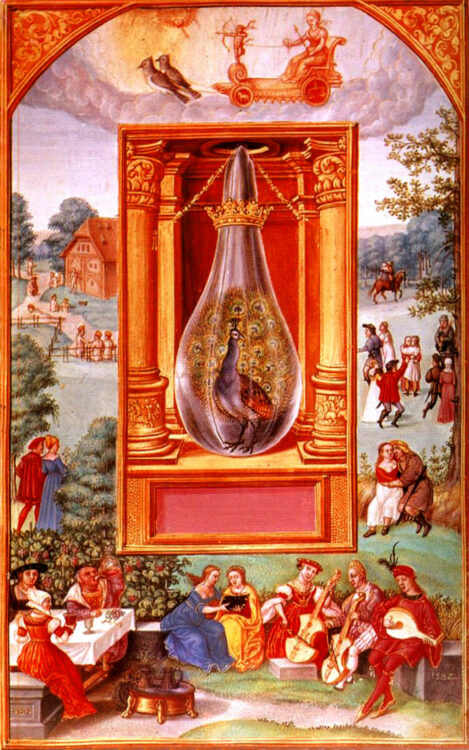

This classical alchemical narrative of the death and rebirth of the king is the subject of “Splendor Solis” (“The Splendour of the Sun”) a beautiful illuminated manuscript which was written in the Central German dialect around 1532–1535 by a certain legendary Renaissance alchemist Salomon Trismosin. It is now at the Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings), Berlin.

The alchemical process in the text incorporates a series of seven flasks, each associated with a planet. Within the flasks a process is shown involving the transformation of bird and animal symbols into the Queen and King.

According to German art historian Jorg Vollnagel: “The Splendor Solis is by no means a laboratory manual, a kind of recipe book for alchemists. Indeed, it is hardly a list of instructions for whipping up a little alchemical soup in the hope of finding a nugget of artificial gold in the pot at the end.

“Rather, the Splendor Solis sets forth the philosophy of alchemy, a world view according to which the human being (the alchemist) exists and acts in harmony with nature, respecting divine creation and at the same time intervening in the processes underlying that creation, all the while supporting its growth with the help of alchemy. Comprised of seven treatises and 22 opulent illustrations, the manuscript revolves around this complex of philosophical concerns, while the business of chemistry itself is accorded a more subordinate role.”

The images from Splendor Solis could be viewed on Wikipedia.

- The Ripley Scroll

The Ripley Scroll from the 17th century is named after George Ripley, mentioned above. (He himself wrote a text known as The Compound of Alchymy way earlier.) It is believed that there are 23 extant copies of the scroll.

According to Christie’s, within the manuscript, “The Green Lion, the Red Lion and the Serpent of Arabia are allegorical representations of various products of distillation and calcination. The integration of alchemy with medieval Christianity and Christian iconography is also evident.”

In the opening illustration, Hermes Trismegistus presents a book about alchemy to George Ripley. The eight roundels show the stages required to create the philosopher’s stone, involving the fusion of sulphur and mercury. Each stage contains a glass flask holding figures, some recalling the scene of the Creation of Eve, and another culminating in a version of The Fall of Man.

You can view the Ripley Scroll on Google Arts and Culture.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.