In 19th-century art, one finds a set of paintings with extremely detailed depictions of the East—especially the Arab world and North Africa. These lands are presented as exotic, sensual and mostly luxurious. The portrayals also appear somewhat stereotypical but the overall effect is very alluring, given the fascination with the foreign and the aura of mystery that the imagery exudes.

This type of art comes under the broader movement of “Orientalism”, that is, an analysis of the East from a Western perspective, literary or visual. [Orientalism is now mostly known via its criticisms by Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said (1935-2003) who regarded it as a position with patronising, imperialist agendas that deemed the East as static and underdeveloped.]

Nancy Demerdash of Princeton University elaborates on the background of the movement:

We also must consider the creation of an “Orient” as a result of imperialism, industrial capitalism, mass consumption, tourism, and settler colonialism in the nineteenth-century. In Europe, trends of cultural appropriation included a consumerist “taste” for materials and objects, like porcelain, textiles, fashion, and carpets, from the Middle East and Asia. For instance, Japonisme was a trend of Japanese-inspired decorative arts, as were Chinoiserie (Chinese-inspired) and Turquerie (Turkish-inspired). The ability of Europeans to purchase and own these materials, to some extent confirmed imperial influence in those areas.

She adds that the phenomenon of World’s Fairs and cultural-national pavilions (like the Crystal Palace in London) supported the goals of colonial expansion. They helped foster the notion of the “Orient” as an “entity to be consumed through its varied pre-industrial craft traditions.”

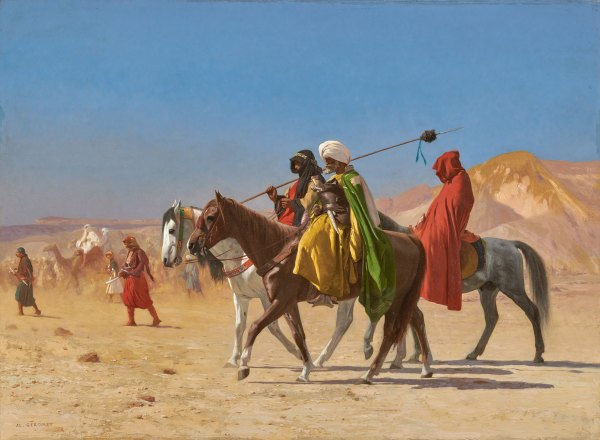

When it comes to “Orientalist” art, we do find some pre-19th-century activity in Europe—an interest in the Moors and the Turks. But much of the output began after the 1750s. Along with colonial and capitalistic aims of the West, the Romanticism of literary figures like Lord Byron played a role in bringing the concept to visual art. Many figures of Orientalist art were French—Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (1845-1902), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). Some happened to be British, Russian and German.

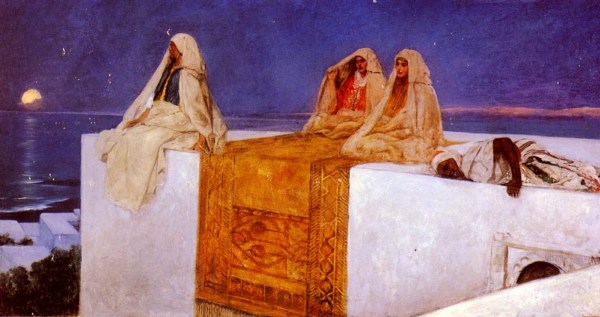

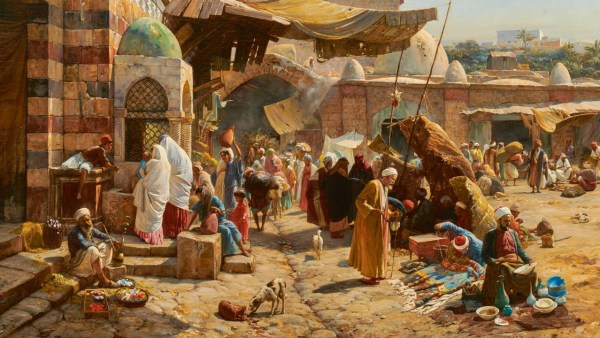

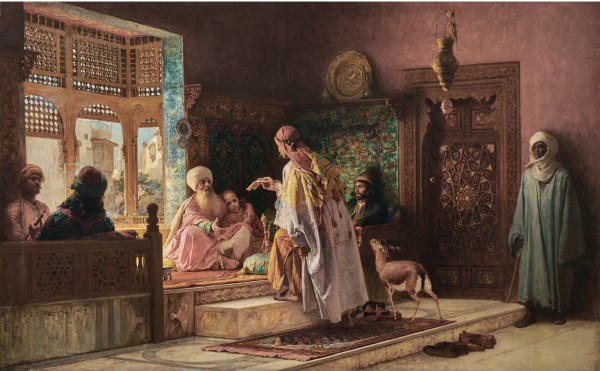

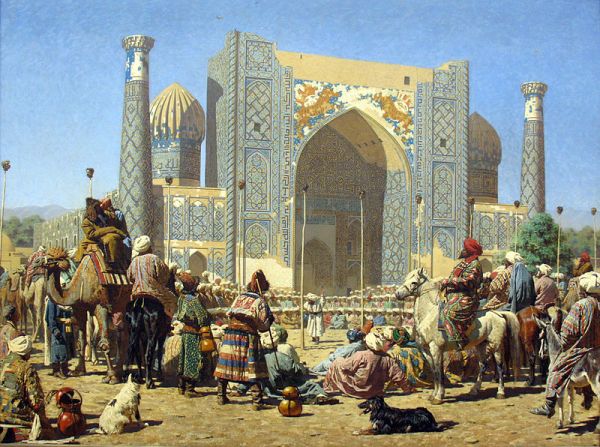

An article on Sotheby’s notes the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, an event that quickly made the Orient more accessible. Several artists were able to travel and interact with people from distant places and observe their lifestyles. The subject matter in Orientalist paintings has a considerable range—palaces, harems, figures with authority, ordinary locals, monuments, the desert, the market. (A few artworks are also controversial for their portrayals of slavery and the supposed sexualisation of minors.) The locations that are featured could be Cairo or Algiers or Jaffa or areas in between big settlements.

In the vast majority of Orientalist paintings, every activity (whether carpet selling or diplomatic meeting or religious instruction) and every element (be it a turban or the moon or intricate Islamic design) is presented with great attention.

An air of fantasy permeates many scenes. The women seem as though they are out of a dream. Jennifer Meagher from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York explains:

Some of the most popular Orientalist genre scenes—and the ones most influential in shaping Western aesthetics—depict harems. Probably denied entrance to authentic seraglios, male artists relied largely on hearsay and imagination, populating opulently decorated interiors with luxuriant odalisques, or female slaves or concubines (many with Western features), reclining in the nude or in Oriental dress. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) never traveled to the East, but used the harem setting to conjure an erotic ideal in his voluptuous odalisques. Beyond their implicit eroticism, harem scenes evoked a sense of cultivated beauty and pampered isolation to which many Westerners aspired.

Despite misgivings about the political and economic standpoints behind Orientalist art—and questions regarding the accuracy of its subject matter—it continues to enchant art lovers and is auctioned off for millions of dollars. Its immediate visual beauty remains unmistakable. And its enduring appeal lies in the way it plays out the whole theatre of being face to face with “the other”. Even though this other is not someone one fully understands, the appearance of it is engaged with in a sense of curiosity and consideration.

Regardless of any stereotype or agenda that these paintings may consciously or unconsciously perpetuate, by looking at them, the viewer can notice a genuine interest in knowing that which is different from the self. And there can be far worse frames of mind people can lock themselves in. Often when nationalisms get so aggressive that they totally refuse to acknowledge—much less encounter—the humanity, the identity, the convictions and the culture of those who come from afar, projects such as Orientalist art can remind us just how exhilarating it can be to cultivate an aspect of openness to the world beyond our domain of comfort and familiarity.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.