Over the past few years, Los Angeles-based painter and sculptor Cleon Peterson (born 1973) has emerged as a very recognisable figure in the visual arts scene, thanks to his repetitive—and unusual—subject matter. His work, he writes on his website, is “chaotic and violent”, showing “clashing figures in a struggle between power and submission in the fluctuating architecture of contemporary society.” He depicts figures that seem human but not entirely. It is as if some sort of biological mutation or technological addition has rendered the beings more animalistic, less rational. By physique, they appear taller, stronger than the average man. Concepts from the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche come to mind: “the superman”, “the will to power”.

Peterson’s art impresses the viewer with the boldness and confidence it displays in terms of form and colour. It also unsettles you as you see more and more iterations of it and get deeper into its content. The artist says: “I’m not an advocate for violence, but I am an advocate for people being un-apathetic in the world today. I’m not a do-gooder, per se—I’m just documenting the world as I see it.”

Reactions to Peterson’s work have been varied. Some believe his art is valuable as it compels one to confront the darkness within oneself, some see it as a celebration of aggression and bloodshed. The whole body of paintings and sculptures is a suitable example of a very important issue within art—that of mere depiction versus conscious endorsement versus caution. Is a certain type of behaviour being presented neutrally as just a part of reality or it is being deliberately encouraged. Or it is serving as a warning—pointing out, “Look, this is what you’re capable of or this is the direction you could possibly go. Be careful.”? It is hard to tell.

One can say that this is an old problem. Readers of the Bible and other holy books—that often show extreme human dysfunction without adequate commentary—may also, at times, find themselves confused.

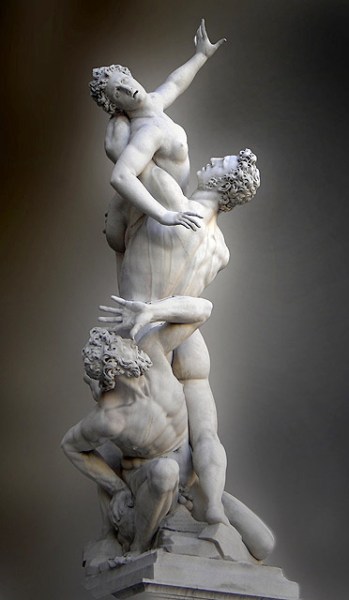

Another relevant case is that of a sculpture titled “Abduction of a Sabine Woman” by Italy-based Flemish artist Giambologna (1529-1608). Created between 1579 and 1583, this artwork is 13 feet in height and is currently placed in a building named Loggia dei Lanzi at a corner of a piazza in Florence, near the famous Uffizi Gallery. The sculpture contains three individuals—a women, followed by two men. The man in the middle is younger than the one at the bottom. He has supposedly taken the woman by force. This is a representation of an incident known as the “The Rape of the Sabine Women” from Roman mythology/the early history of Rome, during which the men of Rome—because there were few women in their own land—committed a mass abduction of females from other cities in the area.

The technical mastery of the artwork is unmistakable, and the dramatic energy intense. But again, the beauty of composition doesn’t solve the ethical dilemma it might place the viewer in. We cannot exactly say if the act of abduction is being objectively recorded or purposefully proposed as an acceptable strategy or pushed forward to instil fear in spectators.

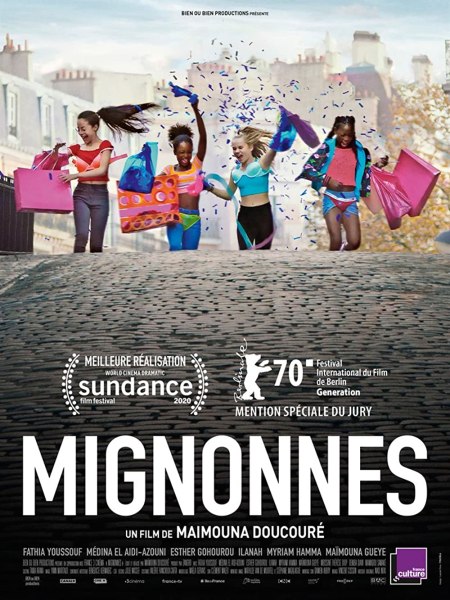

Speaking of cinema, a recent movie that leaves behind a grey territory is the French Netflix feature Mignonnes (2020)—translated as “Cuties” about a preteen Senegalese-French girl and her life between conservative Islam and internet culture—twerking included. The director of the film has reportedly explained: “Our girls see that the more a woman is overly sexualised on social media, the more she’s successful. And the children just imitate what they see, trying to achieve the same result without understanding the meaning, and yeah, it’s dangerous.” But the manner in which pre-adolescents were portrayed in her own film to make her point left audiences perplexed as to what her original motive actually was. An article on Vox capture the controversy well: “A movie critiquing the sexualization of young girls is accused of doing the thing it criticizes.”

In cases like the above, even if the artist’s intent is good, there will always be a section of the audience that may be so attracted to the representation of a harmful behaviour that they may end up imitating it, instead of wanting to prevent it. At the same time, it is impractical to completely censor such portrayals.

Creators who wish to illustrate morally questionable elements of human nature starkly may take several steps to minimise the chances of their work being interpreted in ways that might turn out to be deleterious for the society. First, they could balance out their oeuvre with visions of peace and accord (example, artists like Cleon Peterson producing work that demonstrate people doing something productive together in harmony). They could provide footnotes or disclaimers or context (as in, those similar to Giambologna installing a note near the site of the artwork itself that makes the message clear). Also, creators may be more energetic in reaching out to the media and initiating the dialogue that they wish to generate prior to the release or unveiling of their work (this seems appropriate for films like Cuties) so that audiences are better prepared for what they are about to confront.

Such steps would result in less scandal—and, therefore, less publicity, and even a little less profit—but they will prove to be more sensible and responsible.