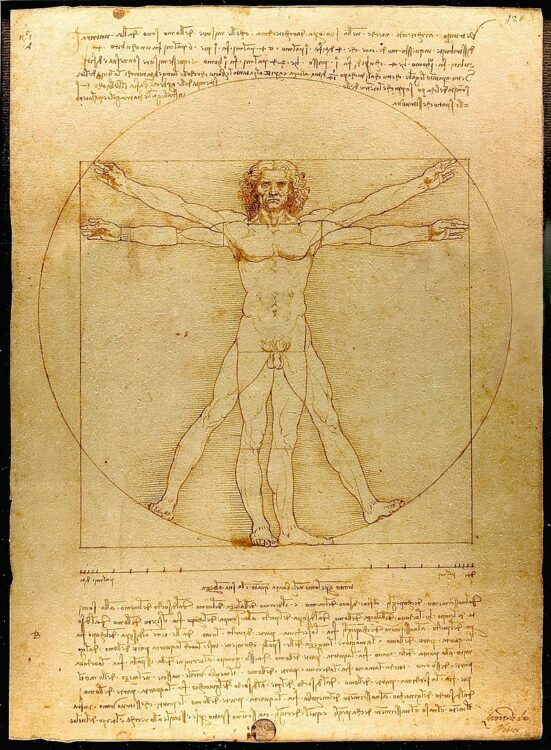

One aspect of modern education that I definitely dislike is the strict compartmentalisation of disciplines. A desire for the division of work for the sake of efficiency has created specialists with narrow areas of expertise. The idea of a “Renaissance Man” (epitomised by Leonardo da Vinci)—a polymath who could be competent in multiple, diverse fields—seems quite alien now. Going back to 15th or 16th century Italy, one sees architecture, painting, illustration that gloriously brought together art and science. Creative professionals seriously explored botany, anatomy, geometry, optics, and more, and incorporated the findings into their work.

In our time, the formal association between art and science seems fairly limited. If there are interesting projects, they most certainly do not dominate headlines like the works of Kaws or Koons.

The careful blending of art and science is a domain with boundless potential. It can bring entirely new audiences to art—those who find it intimidating and feel alienated from it, those who find it not very useful or serious, those who have had no experience with it. School-going children and their parents are certainly demographics that may be drawn to multi-disciplinary projects—“science” being the force that could pull them over, “art” turning out to be a pleasant discovery.

Using examples, here I will outline a few broad topics that artists interested in exploring science could consider. Back in 2020, I did mention how artists could explore climate and ecology (https://melbourneartclass.com/how-artists-could-explore-climate-and-ecology/) and highlighted four individuals. Here the discussion will include and go beyond biology.

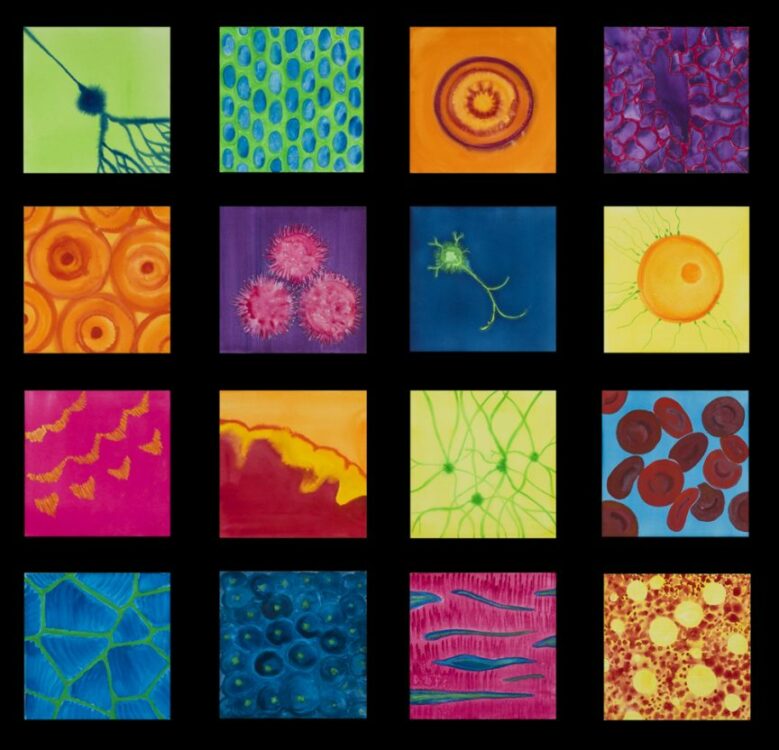

- The Microscopic World

Structures and activities at the molecular and cellular level can be wonderful subject matters if they are taken out of the cold, clinical setting of a laboratory and projected in a more poetic context. For instance, Washington, DC-based Michele Banks has an artwork in which she has assembled fourteen small squares depicting minute patterns inside the body into a single whole titled “Portrait of a Human”.

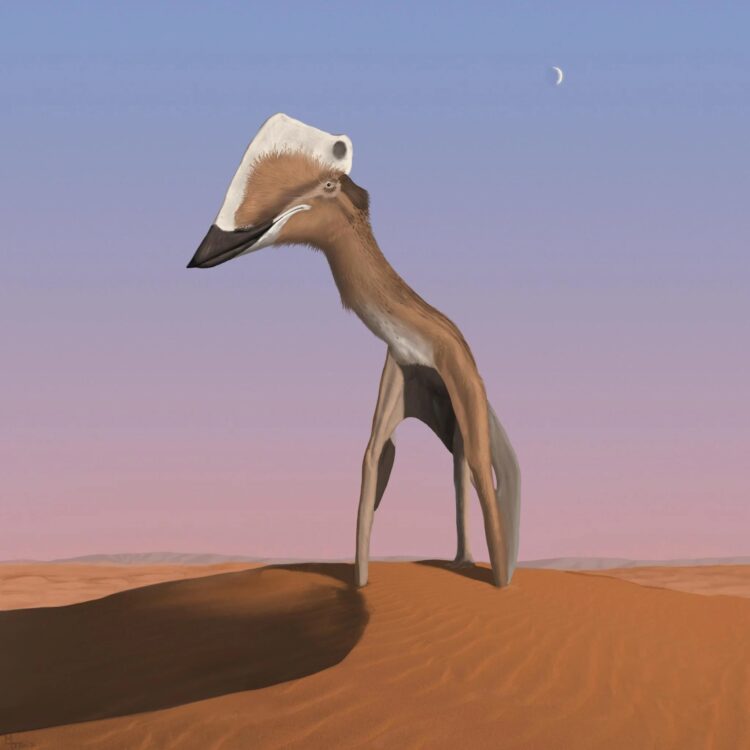

- Organisms from the Deep History of the Earth

The age of Earth is about 4.54 billion years. It is believed that life emerged 3.5 billion years ago. The first human ancestors appeared only between five million and seven million years ago. The massive space and time in the middle contained countless interesting creatures, impressions of many of which have been determined via fossils.

In the academic world, there is a term for the visual reconstructions of prehistoric environmental conditions and long-extinct animals like dinosaurs and mammoths with the help of scientific data—”paleoart”. It is an exciting but hugely overlooked and underappreciated genre of art. Paleoartists spend hours upon hours in research but their work remains limited to few textbooks and encyclopedia, never really achieving mass acceptance. A more popular audience for paleoart, I believe, may be achieved if the visual reconstructions are paired with good and accessible storytelling. For instance, as in the image “Giant Takes a Gander” by US paleoartist and natural history illustrator Midiaou Diallo. It shows an “azhdarchid pterosaur” (a type of flying reptile), which was a huge creature with a wingspan comparable to that of a small aircraft and height akin to giraffes when standing. Here a large male has landed in the Nemegt region of Mongolia (in the Gobi Desert) during the Late Cretaceous period (100 to 66 million years ago on the geologic time scale), stretching his legs on a sand dune far from home. There’s no reason why something like this should not make it to somebody’s living room, leaving them with a greater sense of awe towards our planet.

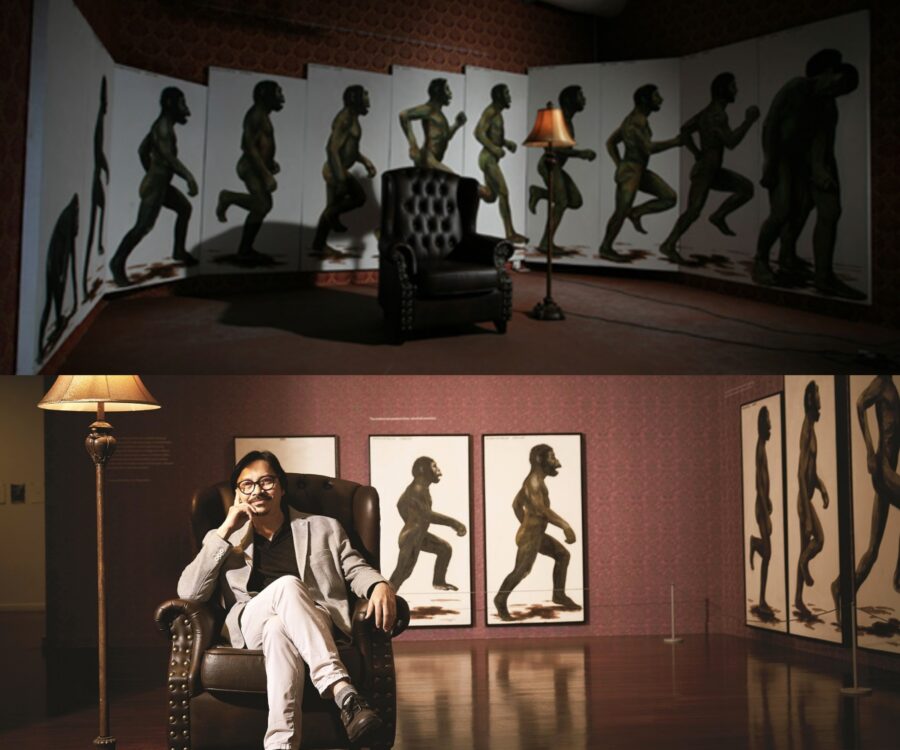

- Human Evolution

Next, the theatre of human evolution across space and time too—which is such a big part of our social discourse—still seems like a considerably underexplored event in art. But if it is to be captured in painting or sculpture, it should not be mere documentation of various stages of development but bring new perspectives that leave viewers reflecting and discussing. In his fascinating 11-panelled work “Mr. D’s Last Meal” (2002), prominent Malaysian artist Ahmad Fuad Osman (born 1969) shows the journey of a crawling primate to Homo sapien. In the final panel, he portrays two humans, one resting on the other. This act makes us wonder: have we become weaker, more dependent on each other as we have progressed? Or is the artist pointing out to our capacity to love and the vulnerability that may arise with it?

- Concepts of Physics

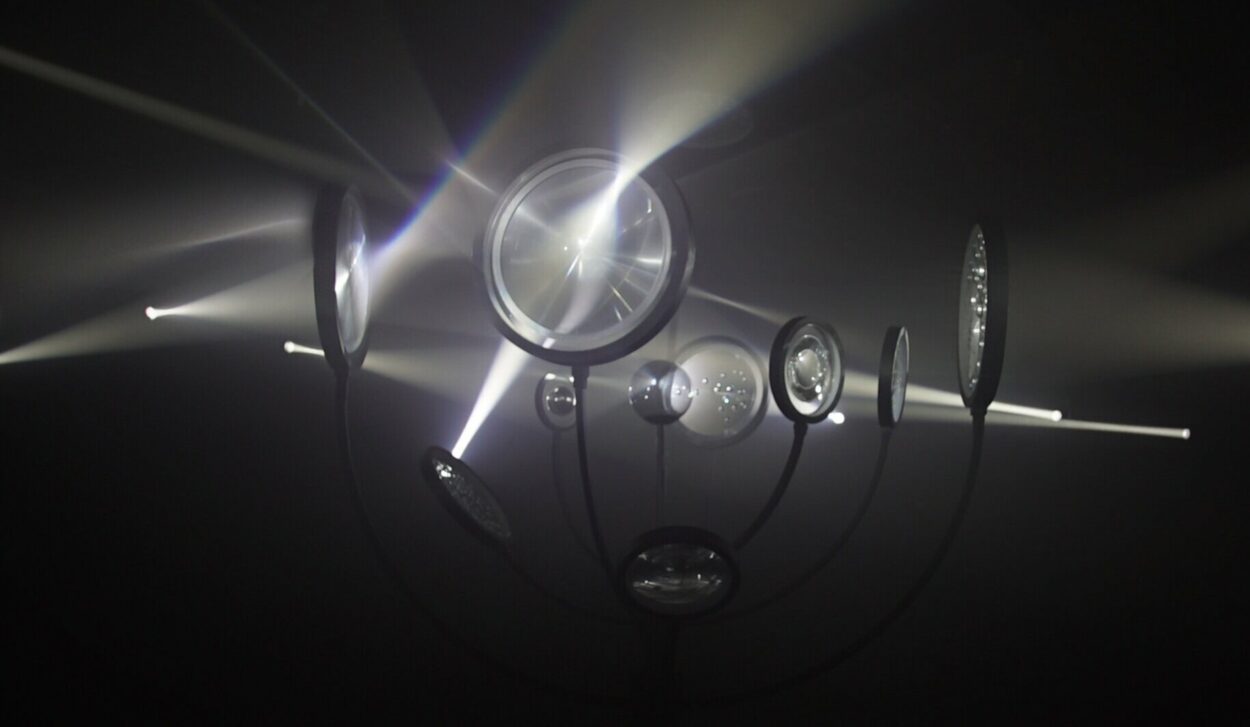

Physics is an area that has produced a massive amount of popular literature over the past few decades, perhaps thanks to Stephen Hawking. At least a basic idea of complex concepts such as black holes and the Higgs boson could be understood by laymen if they put enough effort in going through the texts available. Installation art, especially, is the medium where some of the concepts may be translated aesthetically. A good example is “Dark Distortions” on the nature of dark matter, created by Dutch artist Thijs Biersteker in collaboration with cosmologist Henk Hoekstra of Leiden University, and European Space Agency.

- Outer Space

Lastly, outer space provides tremendous opportunity for art. Artists may create representations of the planets and stars but the cosmos in its vastness and mystery can be a gift, much like the human body, for much poetic and philosophical expression that can take various forms. There is no fixed way in which artists may depict our knowledge (and lack thereof) of the universe. (Even in the case of aliens, nobody says that they must only be drawn with long green faces and large eyes.)

Here I find the famous black monolith from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) very fitting.

It is such a fascinating symbol of our limitation in the face of the unknown but also speaks of curiosity. What exactly does it stand for? Extraterrestrial intelligence, divinity? It’s terrifying but also hope-giving. It could mean anything. Its massive success in cinematic history indicates that there is great scope for art on our conception of the cosmos and relation to it.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.