For more than a year now, I have been regularly watching an unusually prolific Indian YouTuber named Ranveer Allahbadia (@BeerBiceps) and enjoying his conversations with guests who may be specialists in a variety of areas—neuroscience, geopolitics, mythology, spirituality, fitness, law and order, media, archaeology, and so on. A Forbes 30 Under 30 achiever, Mumbai-based Allahbadia runs multiple startups and produces podcasts in both English and Hindi. His approachable, unassuming character, genuine sense of curiosity, and commitment to personal development have won him a large online following.

As a content creator dedicated to constantly maintaining and growing his audience, he has to balance topics that listeners/viewers are already familiar with and want more of with those that might be new to them. Allahbadia admits that he gets the greatest engagement on content that is “dark”, an umbrella term that includes explorations of the unknown and the mysterious (not necessarily harmful phenomena—for instance, the possibilities of unusual beings like masters of meditation who may be over 200 years old hiding in a distant mountain range) along with that which might be downright sinister and scary—extreme spiritualities, paranormal activities, the occult, accounts of possession, black magic, dissections of evil (in dictatorial regimes, in ancient texts).

The synchronisation works very well—somebody interested in the Tantric path of Hinduism or ghosthunting might end up clicking on an interview with an astrophysicist or a police officer. So audience engagement is a major reason behind the dark content but it’s not the only one—given how passionately Allahbadia publishes this material. He has said that these topics help him confront the fears he had as a child and a young adult. They enable him to understand “light” better, all that is good and wholesome. The process is very “cathartic” for him. I found this quite thought-provoking, and have been considering how narratives—visual or literary, fictional or non-fictional—help us release our emotions in an intense yet safe manner.

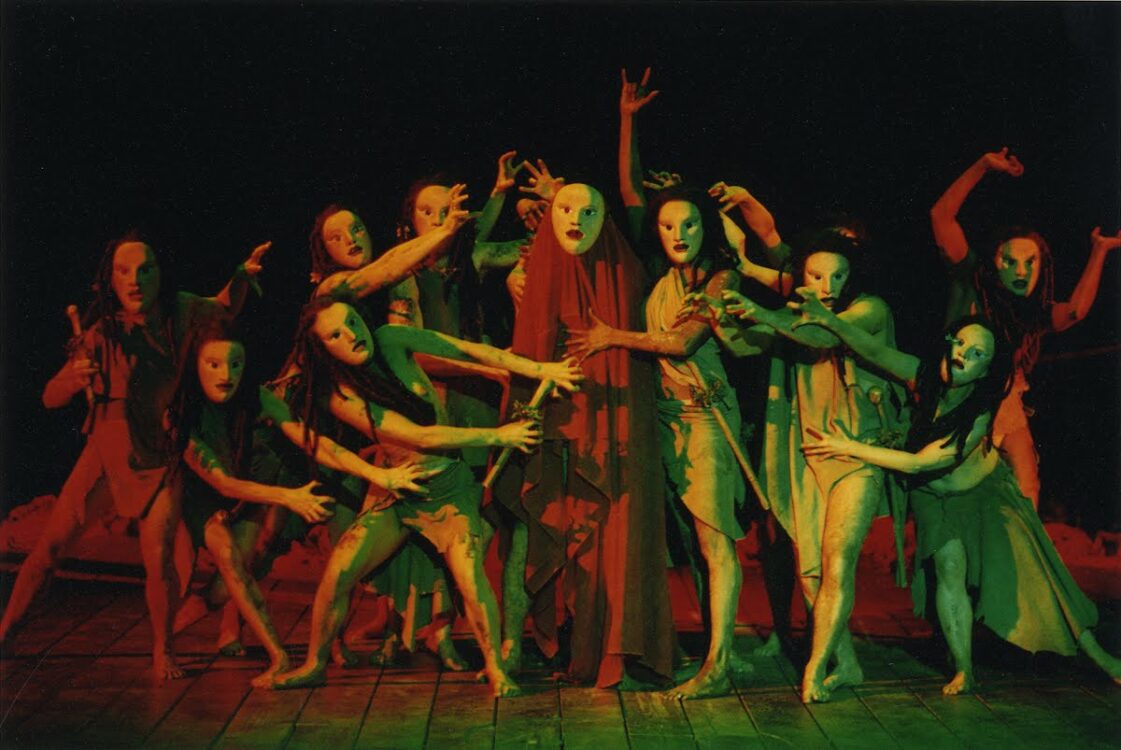

“Catharsis” is a concept I remember learning about in a film class as an undergraduate, which my lecturer explained with regard to ancient Greek tragedy. In the simplest sense it seemed like a sense of “relief” felt by members of the audience when they witnessed characters living out feelings that they themselves had within them (especially negative and repressed). Seeing somebody else cope with the aftermath of situations like betrayal or ostracism helped the viewer find expression for—and, to an extent, manage—their own anxieties. The word comes from the Greek root “kathaírein”, which means “to cleanse”.

An article on the Wall Street Journal considers catharsis as a “technology that can maximise our mental health and happiness”. The writer mentions that this was an observation made by Aristotle way back around 335 BC in his Poetics.

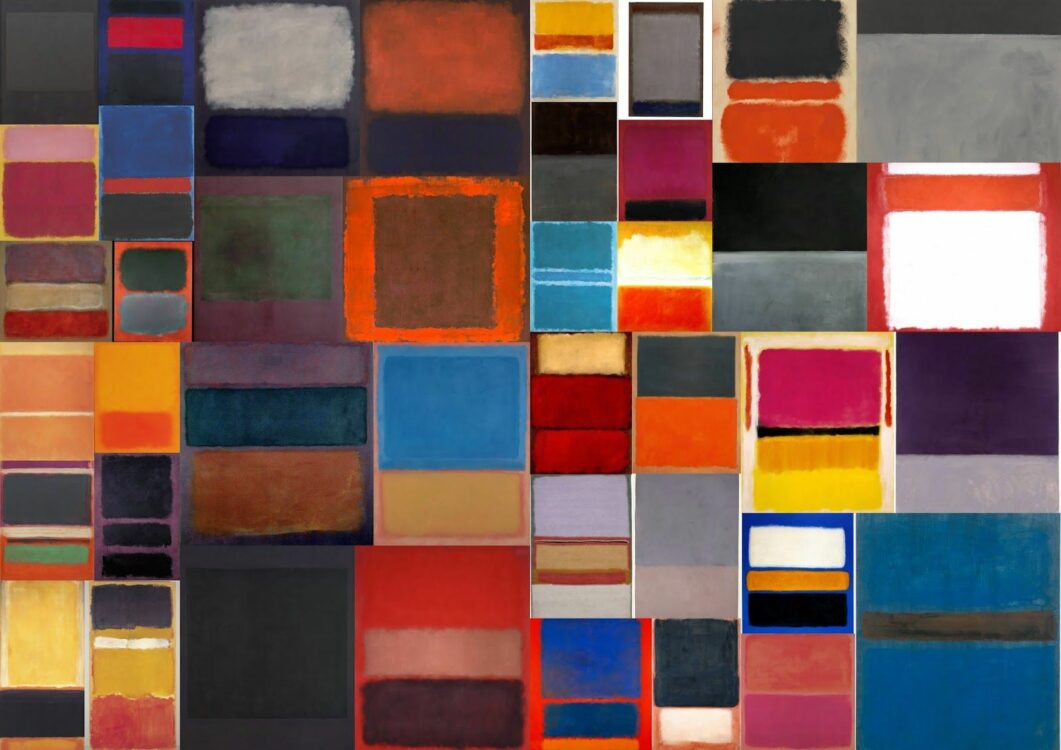

Drama or literature can give strong experiences as it absorbs people in the story through time but visual art, which demands a shorter attention span, can also lead to equally powerful effects. The first painter who comes to mind here is Mark Rothko (1903-1970). His paintings are known for bringing people to tears—which was indeed his intention. “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on,” he said. “And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions….If you…are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point.”

The cathartic possibility of art is an area that artists who want to create work capable of moving people at a personal level could consider actively. We all know that fast-paced modern society—with its migrations, competition and fragile relationships—can leave every other person with mental health issues that they often keep hidden, as direct articulation of these might be easily deemed a character flaw, an evasion of responsibility.

Helping the audience come face to face with their upsetting buried emotions can be profoundly rewarding for an artist, as a recent Instagram post by The School of Life, London pointed: “Feelings get less strong, not stronger, once they’ve been acknowledged.”

But how to know which negative emotion exactly to paint or sculpt? I believe there are a couple of ways in which one can determine that: first, of course, by looking within the self and seeing what episodes have troubled one the most (anything from bullying in childhood to rejection as an adult); second, by looking beyond the self to those whose life story one has engaged with at a deep level, non-judgementally and from an aspect of true humility (these could be family or friends or colleagues, even a stranger whose memoir one has read or encountered during travels who might have confided some traumatic event). In either case, giving good thought to the narrative and then translating it in the most natural manner possible onto one’s chosen medium.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.