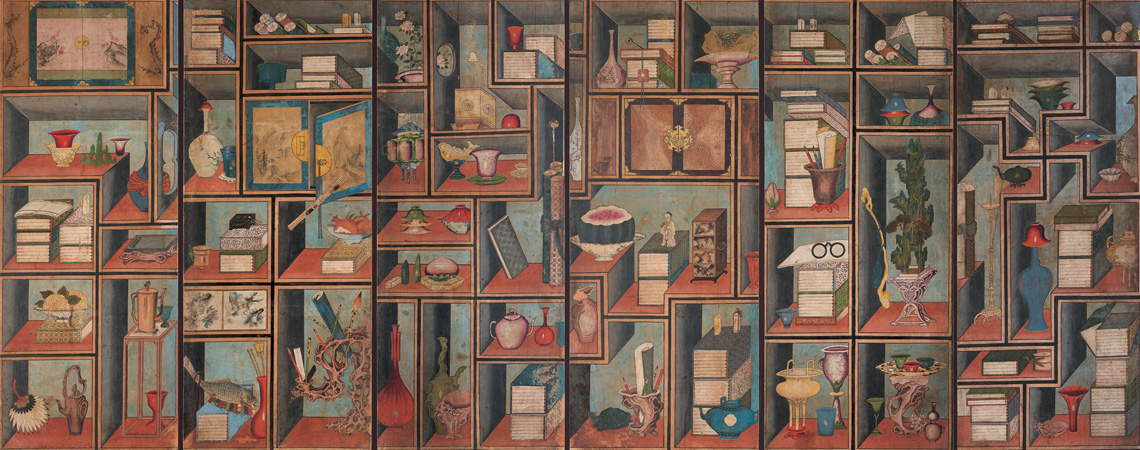

Chaekgeori, the Scholar’s Accoutrements. Late 18th to early 19th-century Korea, The Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea.

Chaekgeori, the Scholar’s Accoutrements. Late 18th to early 19th-century Korea, The Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea.

Some time ago, while searching for Korean art history I discovered a tradition of still-life painting named “chaekgeori” (pronounced Check-oh-ree; literally “books and things”) that instantly caught my attention. Having emerged during the Joseon period (1392-1897)—and flourishing mainly between 1750 and 1950—chaekgeori is quite different from Western practices in the same genre. Its subject matter is more organised than the natural bounty and domestic luxury of the Dutch Golden Age. It is less dramatic than “vanitas” and “memento mori”; instead of contemplating the ephemerality of matter and the inevitability of death, it quietly concentrates on the here and now. A visual parallel could be drawn with portrayals of cabinets of curiosities but the big dissimilarity in this case is that chaekgeori displays the objects that are part of everyday life and not rare and irreplaceable. Chaekgeori celebrates material commodities—but juxtaposed with imagery of 20th-century American consumerism, which attempts the same at a mechanical, mass level—it appears more poetic, sophisticated and personal. The genre, it turns out, is rooted in the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) of China, wherein the emperors maintained a practice of collecting special items like calligraphic scrolls, ritual vessels and decorative objects. Furthermore, the pictorial layout of the genre is inspired by Confucian ideals of discipline that were followed in Korea.

Chaekgeori from the late 19th century, private collection.

The Joseon King Jeongjo (1752-1800), who promoted the style, was a bibliophile encouraging learning and studiousness. Chaekgeori first became popular among the aristocratic class—representing knowledge and power—and was later embraced by commoners. The artworks usually feature multi-panelled folding screens, depicting shelves with books, vases, stationery and other items. The compositions are executed with a sense of perspective and depth—techniques borrowed from Western art. The genre continues today. Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna ran an exhibition titled “Our shelves Our selves” (April 2022 to April 2023) that included contemporary Korean artists exploring the style in different ways.

Chaekgeori from the late 19th century, private collection.

What is fascinating about chaekgeori is its intentionality. For too long we have heard the phrase “art for art’s sake”, and while it has its place in the world of creativity, we also need to balance it with art that can effect positive changes in society made by creators confident about their missions. Chaekgeori is boldly didactic but not in a direct or oppressive way. It is gentle in its espousal of a lifestyle dedicated to curiosity, education, order and cleanliness. The visual culture we are exposed to greatly influences our thought processes, habits, activities, mental and physical health—as we are all aware via the countless debates around the impact of social media. It, therefore, makes sense to conceive and disseminate visual art that can orient the masses to higher goals and better living.

In an essay for the International Institute for Asian Studies in Leiden, the Netherlands, Jinyoung Jin (Director of Cultural Programs, The Charles B. Wang Center, Stony Brook University, NY) writes: “One can say that chaekgeori paintings not only have the ability to teach and inspire, but they also possess the power to shape the values of a society.”

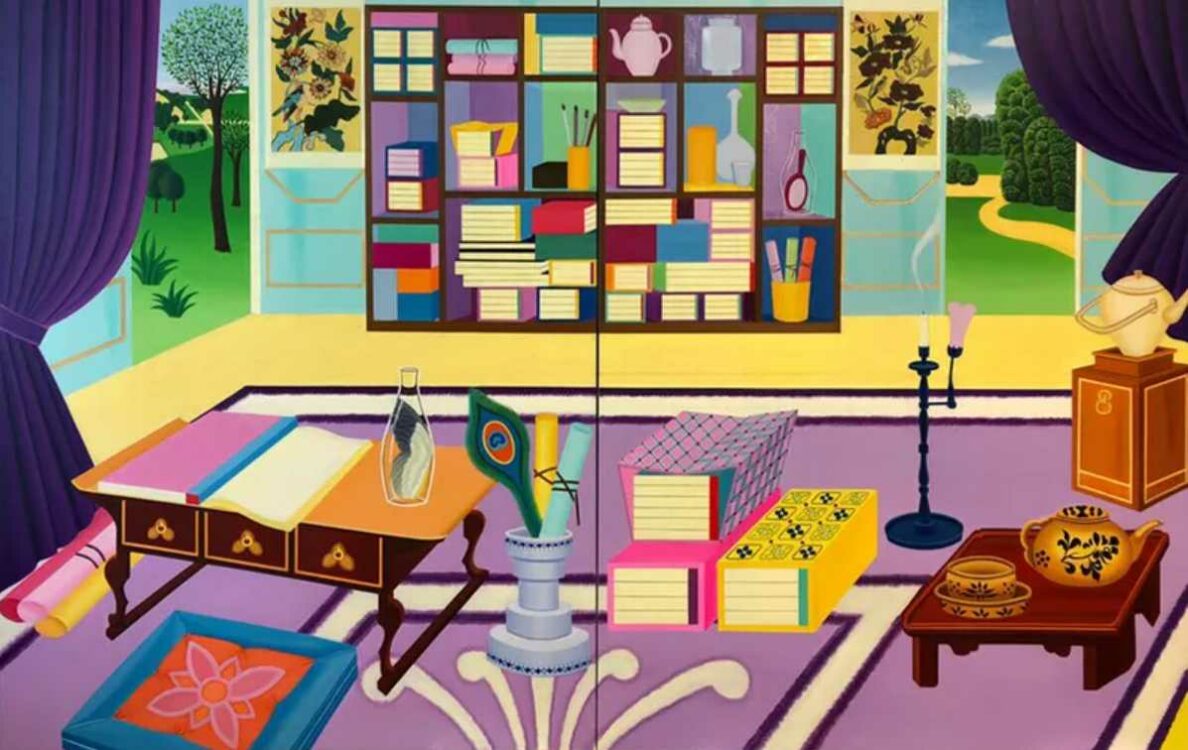

A contemporary chaekgeori titled “The Pleasure of Contemplation: A Room with Chaekgeori and Desk” (2019) by Nam Kyung Min (born 1969).

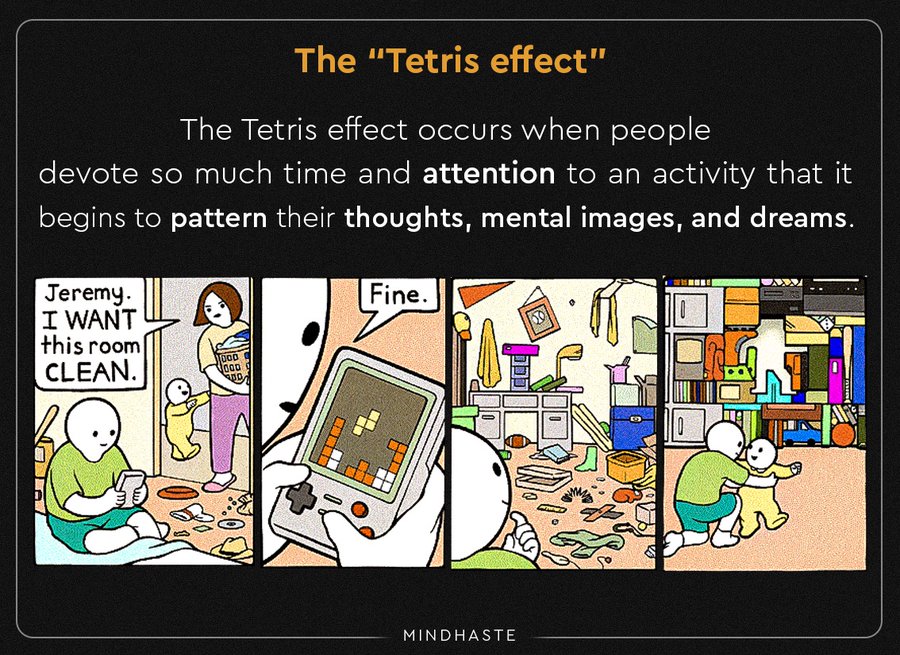

What we perceive and take in from our outer environment arranges and moulds us internally—and this then determines the way we behave and what we put out externally. I have been thinking about this fact lately, having come across the “Tetris effect” (named after the video game Tetris), which, according to Wikipedia, “occurs when people devote so much time and attention to an activity that it begins to pattern their thoughts, mental images, and dreams.” Tetris is a “block-dropping arcade-styled puzzle video game”. The imagery of neatly arranged blocks on the screen can cultivate a psychological inclination in the player/viewer towards neat arrangement in general, which they might want to reproduce and impress upon their physical ambience.

An illustration of the Tetris Effect via Twitter.

Applying this phenomenon to art like chaekgeori, I believe that engagement with imagery that celebrates and advocates edification, structure, and pleasure of possessing meaningful objects can considerably lift people from the unhealthy muddle that they frequently find themselves in when interacting with the chaos of the online world. It can refine their aesthetic tastes and equip them with the resources needed to, in turn, become creators of beautiful content.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.