The word “prehistoric” is very popular but when it comes to art made before the advent of settled life and writing systems, I try not to use it. Many believe that history officially begins with scripted records of human life and culture in the Ancient Near East around 6000-4000 years before the present. This somehow implies that the time prior to that period isn’t included in the grand narrative of the human race. But we have so much evidence available of human consciousness and creativity from the deep past…30,000 years ago, 10,000 years ago—not written accounts on tablets, certainly, but drawings and figurines, signs and symbols that speak volumes. All that cannot not be a part of history. That’s why I prefer the word “preliterate” over “prehistoric”.

Here I will examine five famous examples of preliterate art from different parts of the world and what they might tell us about our ancestors. Very little is known about the cultural context of these hunter-gatherer societies. The works may have had a ceremonial or merely decorative function. Despite the lack of clarity, we might deduce something precious about the human condition by exploring them.

The first artwork that comes to my mind is the “Cave of the Hands” from southern Argentina, about 13,000 years old. These stencilled paintings of dozens of hands (the pigments, it is believed, were sprayed through bone pipes) highlight our inherently social identity, how we must band together for safety and survival. They also indicate our desire to be remembered—as in “I was here”.

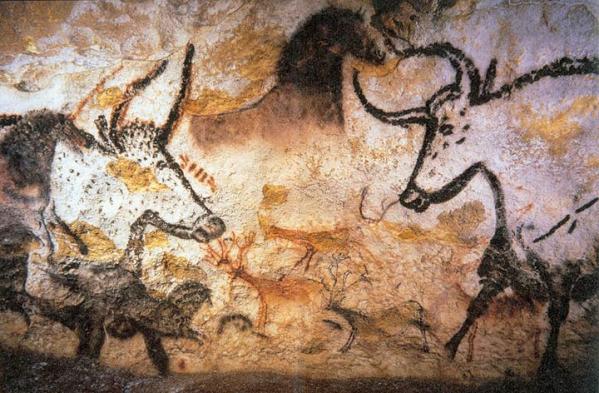

Another cave I think of is Lascaux in southwestern France, which has paintings of wild animals going back 17,000 years. Some observers have linked them to an idea known as “sympathetic magic”—the term was first used by Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist James George Frazer (1854-1941).

Sympathetic magic means a kind of procedure aimed at bringing good luck to the hunters. It could have been performed by shaman-like personalities in a state of trance believing that “ritual actions imitate the real ones you wish to bring about”, that by visualising and meditating on big game, a community will be able to encounter and capture them for real.

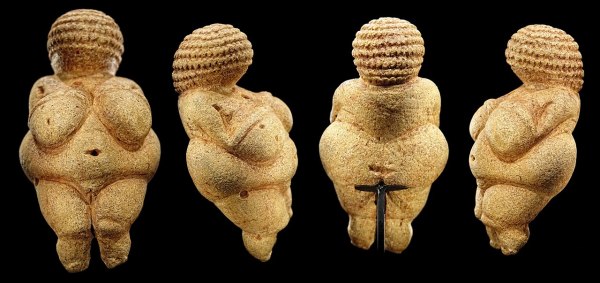

Next, I think of 25,000-year-old “Venus of Willendorf” (Willendorf being a village in northeastern Austria)—a 4.4-inch-tall statuette that was discovered during excavations by Austro-Hungarian archaeologist Josef Szombathy (1853-1943) and others in 1908. This female figurine with plaited hair or headdress and large body could be a mother goddess—that is, a personification of creative forces, fertility, the plenitude of nature found in many cultures, primitive and advanced.

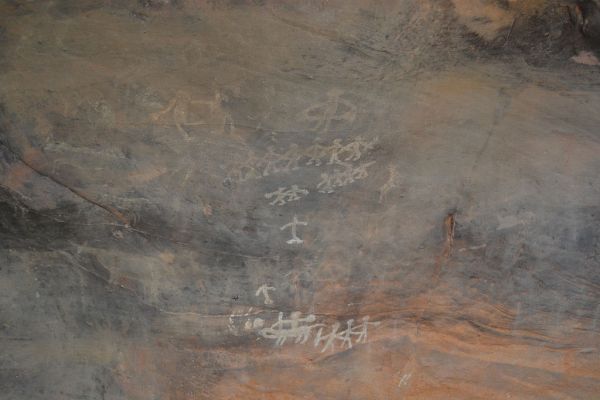

Fourth example is that of the paintings found at the Bhimbetka rock shelters, located in the Raisen district of the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. About 10,000 years old, these depict animals like horses, bison and deer, weapons like arrows, shields and swords, scenes of hunting and also, interestingly, dancing. They give us a glimpse into a slightly more developed community. Here we understand that even with a harsh existence devoid of the comforts and luxuries of civilisation, our ancestors could make room for entertainment and take time out for fun.

Lastly, I have chosen the Ain Sakhri Lovers, a 102 mm high figurine—now at the British Museum—from a cave near Bethlehem, discovered in 1933 by René Neuville, a French consul in Jerusalem. This is the oldest known representation of a copulating couple. It is also a phallic symbol. Like the Venus of Willendorf, it can be said to denote fertility but within a relational framework.

When observed from different perspectives, it looks like different sexual organs—breasts (top), penis (side), vagina (bottom), also testicles. The artwork is about 11,000 years old and belongs to the Natufian culture of the Levant that was known for its semi-sedentary lifestyle even before the dawn of agriculture. Archaeologist Ian Hodder of Stanford University has interesting thoughts on the entwined figures:

The Natufian culture is really before fully domesticated plants and animals, but you already have a sedentary society. This particular object, because of its focus on humans and human sexuality in such a clear way, is part of that general shift towards a greater concern with domesticating the mind, domesticating humans, domesticating human society, being more concerned with human relationships, rather than with the relationships between humans and wild animals, and the relationships between wild animals themselves.

British art historian Neil MacGregor writes that to him the tenderness of the embracing figures suggests not so much reproductive vigour but love. People were beginning to settle and form more stable families and “perhaps this is the first moment in history when a mate could become a husband or a wife”. From this point onwards you must make an effort to continue the species, not in a purely animal way as did those before you, but within the structure of a more definite, committed interpersonal dynamic.

These are only five. Every example of preliterate art can lead to a contemplative or enlightening experience if we engage with it deeply enough.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.