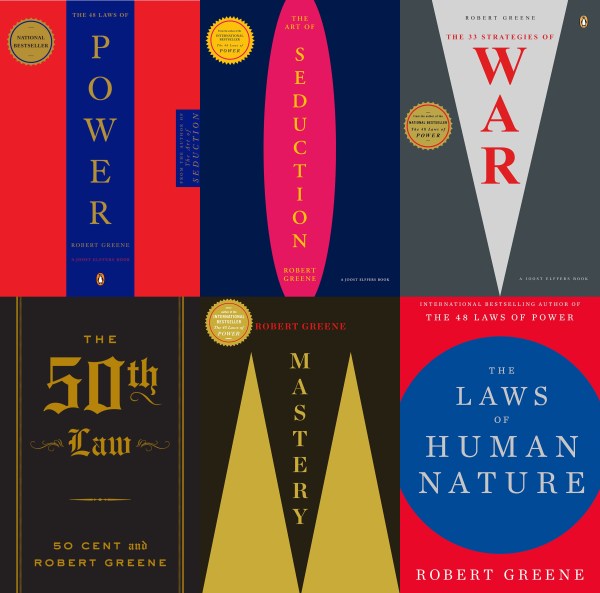

One of my favourite contemporary thinkers is the American author Robert Greene (born 1959)—who has produced the bestsellers The 48 Laws of Power (1998), The Art of Seduction (2001), The 33 Strategies of War (2006), The 50th Law (2009)—this one written with the rapper 50 Cent–Mastery (2012) and The Laws of Human Nature (2018).

Given his subject matter, Greene is a controversial figure. Some people are quick to dismiss his ideas as manipulative and amoral. But that is not the impression I have formed of him after reading a good deal of his work and listening to dozens of his interviews. It’s a joy to engage with his vast knowledge of psychology, history, philosophy and literature.

Greene’s is an unusually wise voice in the realm of self-help and personal development. He is not one of those just-believe-it-and-you-will-achieve-it gurus. He also isn’t about just-work-hard-and-you-will-certainly-get-it. Sure, our optimistic mindsets and efforts are crucial factors behind our success. But hope and industriousness, no matter how potent, may not be enough to melt other people’s “resistances”. People have egos, they are the centres of their own universe. They have deeply held beliefs, prejudices and proclivities. If we want to win them over to our side—as romantic partners, as audiences, as customers, as collaborators, as supporters—we must be careful in what we say or do before them and how. We must learn up the art and science of persuasion.

Greene is passionate about equipping his readers with practical tools that can help them navigate a world the dominant forces of which might not always be in their favour. He doesn’t want us to go beyond good and evil or alter the essence of our identity. We don’t have to be wicked or fake, only skilful and strategic.

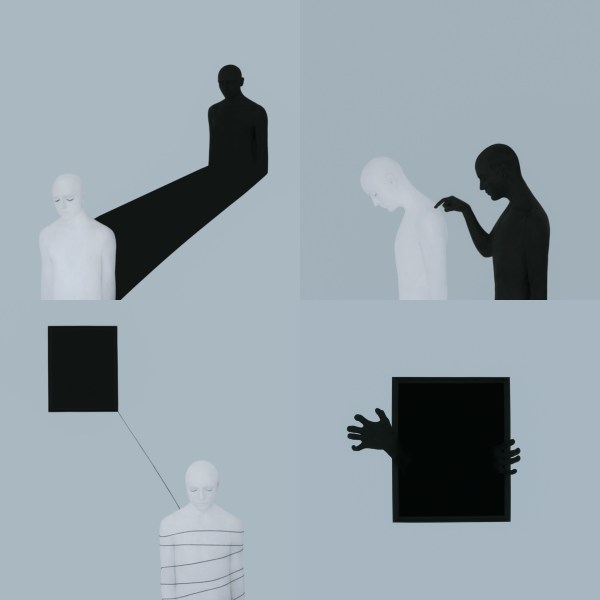

Of late, Greene has been talking a lot about the “dark side” and why it needs to be mastered if we wish to achieve great things in life. This dark side isn’t some dualistic evil half to your good half—it is much more complex than that. It is related to the concept of “the shadow self” proposed by the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Jung (1875-1961). Our shadow is that part of us that lurks beneath our polite and affable exterior. It could be composed of impulses that we may consider both immoral (say, a desire for extramarital affairs) and moral (indignation at the economic inequality of the world). It may be wayward, insecure, selfish, passionately righteous—whatever it is the best way to understand the shadow is that it is carefully concealed from public view.

If the shadow lies repressed or denied, isn’t confronted or disciplined, it leaks out in ways that we might regret later—during touchy moods, in offhand comments, as irrational and irresponsible behaviour…suddenly in your late 20s you get addicted to alcohol and you don’t know why or at the age of 45 you leave your steady job and family and elope with a 19-year-old, destroying everything you’ve worked so hard to build all along.

Interestingly, because of its energetic nature, the shadow can act as fuel for extraordinary feats. Greene himself attributes his accomplishments to careful channelling of his dark side. Before becoming a writer, he’d tried 80 or so jobs across America and Europe—among them, a construction worker, translator, magazine editor and Hollywood writer. The Hollywood stint proved to be an important point in his life. Despite his excellent performance, he ended up getting fired on account of office politics. The experience left him bitter and frustrated.

It is easy for us to accept defeat and sink into self-pity after such incidents but that’s a waste. Dissatisfaction, disappointment, irritation, anger—such emotions have a hidden generative force. In fact, many times the impetus provided by these feelings is even stronger than the motivation that might arise from straightforward love or gratitude or bliss or contentment. Dark energy could be metamorphosed into something productive if it is dedicated to the service of a higher purpose, a bigger vision, a worthy cause or movement.

Instead of directing it inward and becoming a prisoner of it, Greene projected the massive hatred he felt towards the hypocrisy and sycophancy he witnessed in the film business outward into the craft of instructive non-fiction. He wrote The 48 Laws of Power to tell people that you do not have to be naïve, you do not have to suffer. You can protect yourself from harm and the machinations of others.

The shadow can be a real gift to those in the arts, whatever their medium. If a person feels aggression—because of a difficult childhood or professional rejection or failed relationships or something else—and if they have it in them to create and construct something new and beautiful, that ability will be magnified and sharpened manyfold if every time there’s a rush of dark energy through their mind and body, they choose to not give in to painful pondering but just courageously pick up a pen or brush or chisel or camera, diverting the power out of their system into the world.

An artist I would like to use as example here is Kevin Diallo (born 1987), a Senegal-born Ivorian-Australian media professional whom I interviewed recently. In his recent installation “Blue” exhibited at Artspace, Sydney, I believe he converts his deep-seated anger into a powerful expression for a greater cause—he lifts up an entire race.

Here’s the description of the project: “The ocean belongs to the semantics of black suffering, from the history of the Atlantic Slave trade to the recent tragedies of African migrants dying in the Mediterranean Sea while seeking refuge on the shores of Europe; black bodies are intrinsically linked with the maritime.

“From May – September 2019 artist Kevin Diallo crossed the Pacific Ocean on a 40ft sailboat from San Diego USA, to Sydney, Australia accompanied by three friends. ‘Blue’ illustrates how the artist attempted to reclaim the ocean as a space to practice resistance and healing.

“The work utilises photography, moving image, installation and sound to situate black normative existence within a space that typically denies blackness—and how the trauma of blackness’ relationship to the ocean can be radically altered to express freedom, joy and opportunity.”

Written by Tulika Bahadur.