A modern artist whom I find very intriguing for philosophical reasons is the Argentine-Italian painter, sculptor and theorist Lucio Fontana (1899-1968). Fontana was the founder of “spatialism”, a movement that he began in Milan in 1947, by way of which he ambitiously sought to synthesise colour, sound, space, movement and time into an innovative variety of art. The ideas of the project were based on his Manifiesto blanco (White Manifesto), a text that he had published a year earlier in Buenos Aires. He intended to abandon traditional forms—like the easel painting—and adopt techniques such as neon lighting and the television. Of late, there has been a great interest in his work on the auction circuit, with one piece of his, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (1964), being sold for $29,173,000 at Christie’s New York in November of 2015.

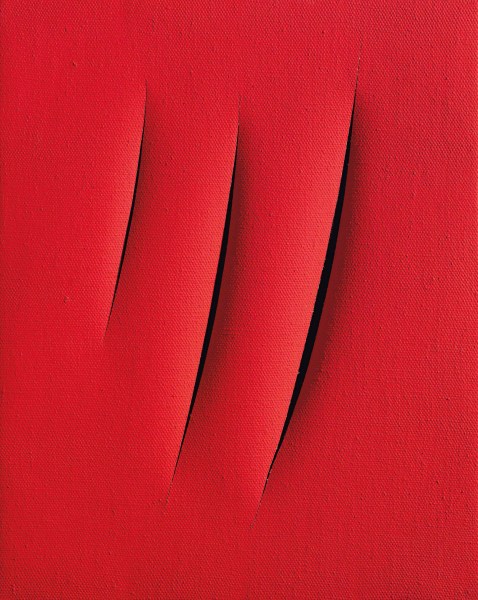

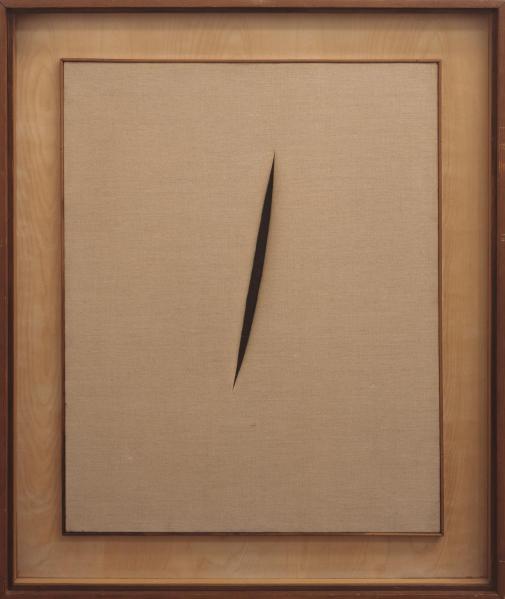

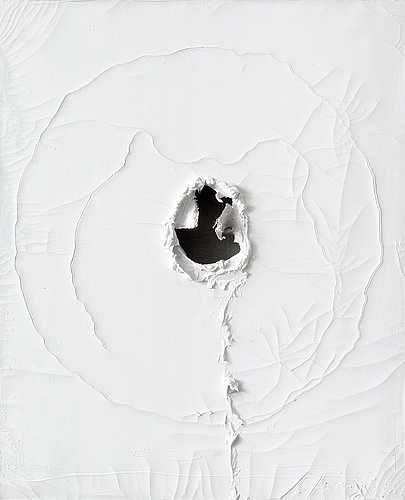

In 1949-50, Fontana began to punch holes (buchi) and cut slashes with razors (tagli) through his canvases. Although they looked spontaneous, they were well-planned, and resembled the “zips” in the abstract expressionist paintings of Barnett Newman (1905-1970).

Multiple interpretations are available of this bold and somewhat baffling artistic act. In an essay for Tate, Philip Shaw, a professor at the University of Leicester, applies a Freudian approach and sees the cuts as representative of female sexuality, the obscure object of desire. The lens of the Second World War is particularly common. In a book titled Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962, Los Angeles-based curator Paul Schimmel situates Fontana’s work within the context of the social and political climate of the postwar period—especially the crisis of humanity resulting from the atomic bomb. As a response, several “international artists,” he points out, “ripped, cut, burned, or affixed objects to the traditionally two-dimensional canvas.” Fontana’s enterprise had been significantly influenced by a Milan that bore the scars of Allied bombings, in which many buildings and monuments had been destroyed.

But in Fontana’s own words, he was alluding to something far greater than just sexuality or war. Through his holes and slashes, he evoked the sublime—that quality in aesthetics felt at encounter with grand things, that is suggestive of awe and terror, both pain and pleasure. He is known to have announced, “I have created an infinite dimension”. He maintained that his experiments were constructive rather than destructive and that his aim was to rupture the surface and enable the viewer to perceive the stuff that lay behind.

Fontana mysteriously said, “I do not want to make a painting; I want to open up space, create a new dimension, tie in the cosmos, as it endlessly expands beyond the confining plane of the picture.” The region behind the picture was an entire plane of being. The artist was playing with the viewer’s understanding of the universe itself. The holes and slashes would either project inwards or outwards, which meant that this new space would either creep in forcefully to an existing domain or it would be reached out to from an existing domain. I cannot help but connect Fontana’s experiments to the wider modern/post-modern worldview of materialism—the position that produces these basic ideas in different guises—matter is the ultimate reality, the spiritual or the supernatural is non-existent, the immaterial mind is an illusion, what you cannot see or hold or measure cannot be true.

Fontana’s ruptured canvases, read within the framework of materialism, suggest a certain suffocation and urgency, a yearning to break free from the prison of a closed, lonely, dreary and insufficiently meaningful universe. They powerfully give expression to the human desire for a taste of transcendence, for “the unknown”, that might still persist after all the calculations have been made, the research papers have been published, experiments have been conducted and surveys have been taken in an arrogantly “scientistic” society.

Written by Tulika Bahadur.