Written by Marco Corsini

We all experience the same material world, albeit at different times and under different circumstances. As artists, we look at the same objects, however, the infinite possibilities our minds present and the possibilities of the medium we use, open up unique paths of interpretation and representation. As observer and representer, we discover a unique version of a perceived reality.

Spanish artist, Antonio López García has mentioned advising art students that they must choose between the objective and the subjective. While some of the nuances of his statement may remain lost in translation, I think what this means for most of us is that we should be aware of the creative tension between representing the world we understand with fidelity (the objective), and the language, the signs, the symbols, techniques, and strategies we use to represent that world (the subjective).

If painting styles sit on a scale between the objective and the subjective, then Hyperrealism and Photorealism would sit at the objective end of the scale and Abstraction would be at the subjective end of the scale. A work really never has just one element alone, objective or subjective, but a mix of both, in different proportions.

For example, Hyperrealism and Photorealism are often images interpreted from a photographic image as the reference used by the artist, which has been used to assist in achieving extreme realist effects. However, although appearing objective, this technical process can introduce its own inherent element of subjectivity. Not only in the choices made (like subject and lighting), but subtly, in its technical means. Standing in front of a work by Juan Ford’s for example, soft, lens effects are evident, translated faithfully and most likely, consciously into the final painted image.

At the other extreme could be a work like that of Sean Scully whose abstraction looks subjective, but has various objective real-world origins. I’ve seen it quoted that Scully’s abstract paintings are inspired by the shapes and the patterns of New York City’s walls, facades, and hoardings. I’ve also read that they originate in Scully’s experience of a checkered Irish society. Either way, there is an objective element to a subjective interpretation.

As artists, we are able to perceive and receive that which we observe. It is the observing that drives us to respond in the creative act, but also our attempt to respond in the same creative act, which drives us back to observe. We inhabit a cycle of receiving from that which we observe and responding, all because we make.

As artists, a creative tension exists between the objective which we observe and perceive as external to us, the objective which we receive, and the subjective elements of our response. It’s tempting to say that an artwork is an entirely subjective product, but if art were entirely subjective, we would not consistently be able to see universal elements in art which we understand and discuss corporately. These elements are a transferral of the objective, the perceived, received by the artist and communicated effectively enough to be referenced by others as an objective real world element. Elements such as Scully’s clashing yet simultaneous association of forms which give us a visual sense of what we may later be told are relationships within a society or urban habitation. We may not know what Scully’s inspiration or intention was but we get a sense of the relationships described through the visual. Or that we get a sense of isolation and irony when viewing the ridiculously bound yet robustly physical masculine figure by Ford, which seems to also represent something of the current male experience. There are real world elements in these artworks which render them in part, reflections of an objective world.

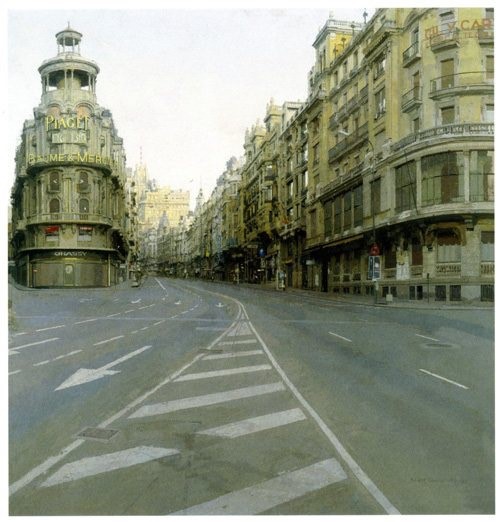

The three painters I have mentioned have all received in some way. Ford, his Australian male locality and subjectivity, his conceptual formation. Scully received from the pattern and form of his society, both in the cityscape and sociologically, also from the development of painting into modernism and abstraction. López García, received from being trained by his uncle when he was a boy and from his encounter with his immediate environment and life. These artists, having received, have also chosen to respond through their art practice, or we could say have chosen to give, because they have not just responded, they have passed something on, as if they themselves have become a conduit of the world. Each artist a unique conduit derived from the tension between objective and subjective.

Vincent van Gogh came to realise that he could receive and give through his immediate surroundings of light, colour and persons in southern France. He opened up to this provision that for him eclipsed, at least for a moment, negative experiences such as mental health struggles and poverty. I am not advocating a cure-all in art, but the fruit of such receiving and subsequent giving was visible in the lines of people that inhabited the National Gallery of Victoria for months during the recent exhibition, Van Gogh and the Seasons.

I adore the reclusive, awkward man, Paul Cézanne. Although just like Van Gogh, he was committed to working from life around him, Cézanne didn’t necessarily represent the world perfectly. To my mind, his paintings were sometimes awkward and flawed, but from the awkwardness and from his unique way of seeing the world, a position developed which translated into great visual poetry in his later work. Cézanne tells me that while my mastery of my craft as a painter may seem slow at times, if I am open to being a student of the painting tradition and if I open myself to receiving from that which is around me, I will eventually respond from my own beautiful position in the world. In giving in this way, I add something to the world.